Tech startups will be enthused by the news that Silicon Valley venture capital (VC) veteran General Catalyst is on the verge of raising US$6 billion (£4.8 billion) for backing new companies. It comes hot on the heels of an announcement from Andreessen Horowitz, another major VC, of a new US$7.2 billion investment fund. These are among the largest fundraisings in years, coming at a time when the VC sector has been going through a lull, with worldwide total investments down from US$644 billion in 2021 to US$286 billion in 2023.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa.

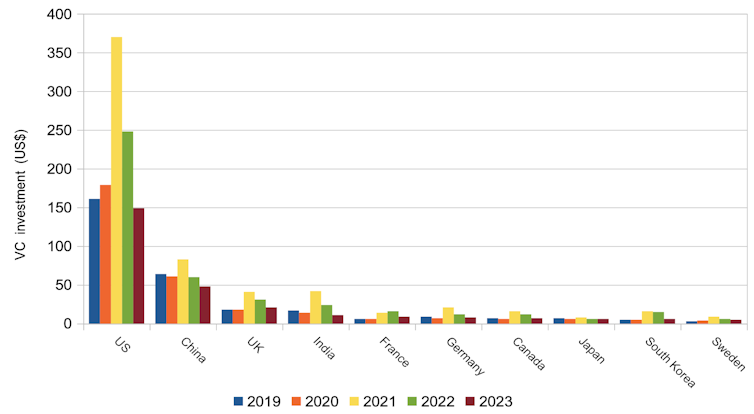

The bad news, depending on where you live, is that most of the proceeds are likely to be invested Stateside. American startups mop up around half of all global VC funding, while Europe and the UK are lucky to see a quarter. This is despite the fact that Europe and the UK have a slightly larger share of world GDP than the US (17% v 16%).

VC investment by country (US$)

This helps to explain why America’s leading three tech firms, Microsoft, Apple and Nvidia, are worth around US$7.5 trillion, while Europe’s equivalents, ASML, SAP and Prosus, are worth some US$700 billion. So what can be done to change this situation?

Silicon Valley’s edge

Silicon Valley’s success can be attributed to a range of mutually reinforcing factors, many of which planted their seeds decades ago. These include lucrative government contracts, entrepreneurial universities nearby, and the accumulation of wealth and talent from tech giants such as Apple, Nvidia, and OpenAI. This kind of head start is difficult to replicate.

US investors often plough millions of dollars into relatively early-stage companies, which are sums that other ecosystems simply cannot match. But startups typically first need to demonstrate traction with customers, usually in the form of sales revenue or user numbers. This is different from tech investment hubs such as Berlin and Scotland, where investors tend to only require a strong team with just an idea for the startup to be considered to have good potential for investment. Our research suggests that this might be an underappreciated reason for Silicon Valley’s success.

Having done in-depth interviews with 63 entrepreneurs and investors across Silicon Valley and Berlin, the different expectations of investors are very noticeable. For instance, the founders of San Francisco-based AirBnb had to use their credit cards to keep the company afloat, and even resorted to selling cereal boxes before eventually securing funding.

Similarly, the founders of food delivery app DoorDash, which is also based in San Francisco, built a full prototype and were making the deliveries themselves for nearly half a year before raising their first round of investment.

This is in stark contrast to European ecosystems. Recent examples from Berlin include language tutor marketplace HeyLama, which secured funding nearly immediately after inception. Meanwhile, pet care startup Rex raised more than US$5 million within months after launching.

And yet, between 2020 and 2022, US$44 billion was invested in early-stage deals in Silicon Valley as opposed to US$5.8 billion in Berlin. Equally, roughly 31% of US but only 19% of European seed-stage startups progress to the next round of fundraising.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that the companies that do not raise follow-on funding fail, but it may help explain why Silicon Valley’s exits amount to US$403 million on average, as opposed to US$53 million in Berlin.

So why is it not the case that US startups struggle more when they have to meet higher expectations to get funded? And could other ecosystems catch up by adopting the same strategy?

The ‘valley of death’

The journey of a business idea from inception to early traction is often referred to as the “valley of death”. During this period, the startup needs to keep developing the business, build the product, and figure out a reliable business model. There is no one-size-fits-all blueprint and many companies fail, either because the idea is not viable or they run out of money.

Silicon Valley’s preferred funding model of investing into startups with traction somewhat decreases the risk of failure for VCs. In the long term this should result in more funds for reinvesting into new startups, which likely helped the whole ecosystem to flourish. There’s also a benefit to those entrepreneurs who can delay fundraising until they can demonstrate traction, since the startup is likely to be worth more. This means they can get more money or give up a smaller percentage of the business.

This would suggest that European startup ecosystems ought to think about moving towards this model. But it comes with a major downside. Few entrepreneurs have enough money to maintain the company through the valley of death – and it tends to be longer and deeper for the most innovative ideas. This is particularly an issue for entrepreneurs from under-represented groups, such as disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds, women and immigrants, who are less likely to have the necessary resources or connections. Thus, adopting the American investment threshold could make the startup world even more inaccessible to them.

To get the benefits of the US system without damaging diversity, there need to be support structures in place, such as incubator and accelerator programmes, to help startups gain traction. Even so, these need to be designed carefully to ensure they signal credibility, and therefore help – rather than hinder – the incubated companies to secure their first round of investment.![]()

Michaela Hruskova, Lecturer in Entrepreneurship, University of Stirling and Katharina Scheidgen, Chair of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.