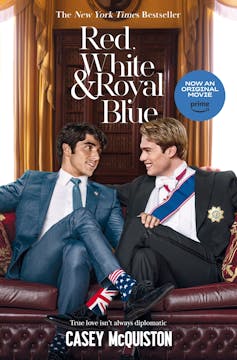

Alex (Taylor Zakhar Perez) and Henry (Nicholas Galitzine) in the film of Casey McQuiston’s Red, White and Royal Blue. Amazon Prime Elizabeth Little, Deakin University

Alex (Taylor Zakhar Perez) and Henry (Nicholas Galitzine) in the film of Casey McQuiston’s Red, White and Royal Blue. Amazon Prime Elizabeth Little, Deakin UniversityA royal romance is once again trending on social media.

This time, it’s a queer royal romance. And it even has its own hashtag: #firstprince

Casey McQuiston’s beloved, bestselling 2019 young adult novel, Red, White and Royal Blue, has just launched as a movie, on Amazon Prime. And fans are excited. The story follows Alex Claremont-Diaz, son of the first female American president, and his developing relationship with Henry, the Prince of Wales.

As a genre, “royal romance” follows many of the regular romance conventions, but must include a member of a royal family or peerage as one of the love interests. Book blogs and Goodreads are full of suggestions for getting your Prince (or Princess) Charming fix.

The queer injection into the young adult royal romance reflects a broader shift in what’s being published and read. Last year, research showed LGBTQ fiction sales in the US jumped 39% from the same period in the previous year. And young adult fiction grew in particular, with 1.3 million more books sold than the previous year.

Alice Oseman’s Heartstopper, a queer teen (graphic novel) love story, adapted for Netflix, is reported to have sold more than eight million copies to date – and even to have “helped keep bookshops afloat” in recent hard times.

A book industry analyst said the young adult queer fiction growth “mirrors a generational shift toward a more open and inclusive attitude toward gender diversity and sexual orientation”.

The popularity – and acceptance – of texts like Red, White and Royal Blue means the desires and fantasies of queer youth are being normalised.

Royal romance tropes

The key to royal romance is it offers readers possibility and transformation on a grand scale: by getting that crown, the main character does not just become royal, they become their best selves – on the world stage.

It’s been more than 20 years since Anne Hathaway graced our screens in the film adaptation of Meg Cabot’s young adult royal romance The Princess Diaries (2001).

The book follows a familiar narrative, where a girl who discovers she is in fact royalty has to be transformed into a princess. Princess Mia grows into herself as she prepares to lead Genovia.

Other familiar tropes of the royal romance include the “surprise reveal”, where one half of a couple’s royal identity is uncovered, like in Netflix’s The Princess Switch.

A viral success

Released in 2019, Casey McQuiston’s book quickly went viral, becoming an instant New York Times bestseller, winning awards and making best books lists. The classic “enemies-to-lovers” romance trope takes on international significance with the offspring of two world leaders involved.

Alex and Henry’s initial dislike for each other boils over and catches media attention after they ruin the cake at a royal wedding. To try to limit the diplomatic and media fall-out, the two have to pretend to be friends – which leads to their budding romance, and discovering their sexuality together. (Alex is bisexual and Henry is gay.)

Casey McQuiston, who identifies as nonbinary, has talked about how straight literature has suggested it’s statistically unlikely for more than one queer person to exist in a story. In Red, White and Royal Blue, multiple queer people not only exist: they include the children of the most powerful people of the world, and become romantically involved.

The social media response to Red, White and Royal Blue clearly demonstrates young people want to see queer romance that reflects their own lives, and their own desires for transformation.

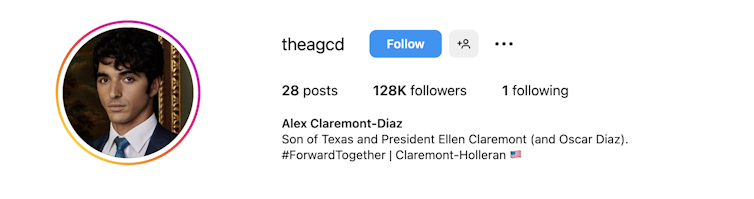

Just in the past week, Prime launched individual Instagram accounts for Prince Henry and Alex. The comments sections have thousands of interactions already.

“Alex you bisexual icon,” wrote one Goodreads reviewer, who described it as “comforting” to read the book while “having my own bisexual panic”. “It has meant so much to me as a queer individual,” wrote another, cited in the same study.

Interestingly, that study found many readers were willing to forgive the book for other things they didn’t like, because they were so excited by the queer representation.

More royal romances that explore difference

Her Royal Highness is a companion story to Hawkins’ first (heteronormative) royal romance novel, Prince Charming (originally titled “Royals”). Hawkins’ choice to explore queer romance was, she says, a response to what fans wanted. And she was keen to “restore balance” and write a tropey rom-com, but with lesbians.

Other young adult royal romances have maintained the focus on boy-girl couples, but engaged with contemporary audiences in other ways, by exploring concerns around class, wealth and gendered expectations.

In Katharine McGee’s American Royals, the House of Washington are the royal family, with Princess Beatrice the heir to the throne. Beatrice, who is in love with her personal bodyguard, goes on a journey of transformation that ends with her choosing her royal duties of love, and seemingly growing up. An important aspect of American Royals is how Beatrice will cope with being the first female monarch, introducing feminist concerns about leadership.

In Kiera Cass’s The Selection, the young adult royal romance meets a dystopian setting, where in a post-apocalyptic world, girls (and boys) vie for the attention of royals, so they can escape rigid caste systems and live in a palace. It’s been described as The Bachelor meets The Hunger Games. In texts like The Selection, the concerns of young people are not limited to romantic tensions, but include body image and status, conflict and poverty.

Even as young adult romances have shifted to include queer perspectives, one key aspect remains the same – teenage love, in all its forms, has the possibility of bringing about true individual transformation.

The young adult royal romance is about so much more than just love-interests-meet-and-get-crown. It’s about young people desiring to be something more, and undergoing a clear transformative journey.

While Mia Thermopolis lost her bushy eyebrows and gained a sleek tiara, her journey was about discovering her true worth.

In Red, White and Royal Blue, Alex and Henry don’t just avoid an international diplomatic disaster by falling in love: they give voice to the desires of queer and diverse youth who want to see a happily-ever-after that looks like them represented on the page, and the screen.

Luckily, these days, there are increasingly more options to choose from.![]()

Elizabeth Little, Early Career Researcher, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.