Some animals, including goats, regularly give birth to two babies at once. Image Source via Getty Images

Some animals, including goats, regularly give birth to two babies at once. Image Source via Getty ImagesWe are faculty members at Mississippi State University College of Veterinary Medicine. We’ve been present for the births of many puppies and kittens over the years – and the animal moms almost always deliver multiples.

But are all those animal siblings who share the same birthday twins?

Twins are two peas in a pod

Twins are defined as two offspring from the same pregnancy.

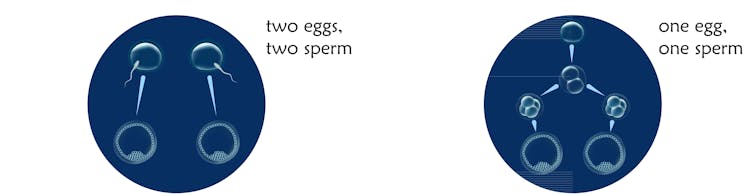

They can be identical, which means a single sperm fertilized a single egg that divided into two separate cells that went on to develop into two identical babies. They share the same DNA, and that’s why the two twins are essentially indistinguishable from each other.

Twins can also be fraternal. That’s the outcome when two separate eggs are fertilized individually at the same time. Each twin has its own set of genes from the mother and the father. One can be male and one can be female. Fraternal twins are basically as similar as any set of siblings.

Fraternal twins originate in two eggs fertilized separately, while identical twins originate in a single fertilized egg that divides to create two embryos. Veronika Zakharova/Science Photo Library via Getty Images

Fraternal twins originate in two eggs fertilized separately, while identical twins originate in a single fertilized egg that divides to create two embryos. Veronika Zakharova/Science Photo Library via Getty ImagesApproximately 3% of human pregnancies in the United States produce twins. Most of those are fraternal – approximately one out of every three pairs of twins is identical.

Multiple babies from one animal mom

Each kind of animal has its own standard number of offspring per birth. People tend to know the most about domesticated species that are kept as pets or farm animals.

One study that surveyed the size of over 10,000 litters among purebred dogs found that the average number of puppies varied by the size of the dog breed. Miniature breed dogs – like chihuahuas and toy poodles, generally weighing less than 10 pounds (4.5 kilograms) – averaged 3.5 puppies per litter. Giant breed dogs – like mastiffs and Great Danes, typically over 100 pounds (45 kilograms) – averaged more than seven puppies per litter.

When a litter of dogs, for instance, consists of only two offspring, people tend to refer to the two puppies as twins. Twins are the most common pregnancy outcome in goats, though mom goats can give birth to a single-born kid or larger litters, too. Sheep frequently have twins, but single-born lambs are more common.

Horses, which are pregnant for 11 to 12 months, and cows, which are pregnant for nine to 10 months, tend to have just one foal or calf at a time – but twins may occur. Veterinarians and ranchers have long believed that it would be financially beneficial to encourage the conception of twins in dairy and beef cattle. Basically the farmer would get two calves for the price of one pregnancy.

But twins in cattle may result in birth complications for the cow and undersized calves with reduced survival rates. Similar risks come with twin pregnancies in horses, which tend to lead to both pregnancy complications that may harm the mare and the birth of weak foals.

DNA holds the answer to what kind of twins

So plenty of animals can give birth to twins. A more complicated question is whether two animal babies born together are identical or fraternal twins.

Biologists believe that identical twins in most animals are very rare. The tricky part is that lots of animal siblings look very, very similar and researchers need to do a DNA test to confirm whether two animals do in fact share all their genes. Only one documented report of identical twin dogs was confirmed by DNA testing. But no one knows for sure how frequently fertilized animal eggs split and grow into identical twin animal babies.

And reproduction is different in various animals. For instance, nine-banded armadillos normally give birth to identical quadruplets. After a mother armadillo releases an egg and it becomes fertilized, it splits into four separate identical cells that develop into identical pups. Its relative, the seven-banded armadillo, can give birth to anywhere from seven to nine identical pups at one time.

There’s still a lot that scientists aren’t sure about when it comes to twins in other species. Since DNA testing is not commonly performed in animals, no one really knows how often identical twins are born. It’s possible – maybe even likely – that identical twins may have been born in some species without anyone’s ever knowing.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Michael Jaffe, Associate Professor of Small Animal Surgery, Mississippi State University and Tracy Jaffe, Assistant Clinical Professor of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.