Tuesday, 28 January 2025

AI can add $4.4 trillion to global economy, but digital divide must be removed: WEF report

Friday, 17 January 2025

World Bank looks to fresh beginning in Sri Lanka

Tuesday, 3 September 2024

India achieves 40th rank in 2023 edition of Global Innovation Index

Wednesday, 26 June 2024

World Bank says 80% of global population will experience slower growth than in pre-COVID decade

- Latest Global Economic Prospects report acknowledges global growth stabilising for first time in three years

- The global economy is expected to stabilise for the first time in three years in 2024—but at a level that is weak by recent historical standards, according to the World Bank’s latest Global Economic Prospects report released on Thursday.

- Global growth is projected to hold steady at 2.6% in 2024 before edging up to an average of 2.7% in 2025-26. That is well below the 3.1% average in the decade before COVID-19. The forecast implies that over the course of 2024-26 countries that collectively account for more than 80% of the world’s population and global GDP would still be growing more slowly than they did in the decade before COVID-19.

- Overall, developing economies are projected to grow 4% on average over 2024-25, slightly slower than in 2023. Growth in low-income economies is expected to accelerate to 5% in 2024 from 3.8% in 2023. However, the forecasts for 2024 growth reflect downgrades in three out of every four low-income economies since January. In advanced economies, growth is set to remain steady at 1.5% in 2024 before rising to 1.7% in 2025.

- “Four years after the upheavals caused by the pandemic, conflicts, inflation, and monetary tightening, it appears that global economic growth is steadying,” said World Bank Group’s Chief Economist and Senior Vice President Indermit Gill. “However, growth is at lower levels than before 2020. Prospects for the world’s poorest economies are even more worrisome. They face punishing levels of debt service, constricting trade possibilities, and costly climate events. Developing economies will have to find ways to encourage private investment, reduce public debt, and improve education, health, and basic infrastructure. The poorest among them—especially the 75 countries eligible for concessional assistance from the International Development Association—will not be able to do this without international support.”

- This year, one in four developing economies is expected to remain poorer than it was on the eve of the pandemic in 2019. This proportion is twice as high for countries in fragile- and conflict-affected situations. Moreover, the income gap between developing economies and advanced economies is set to widen in nearly half of developing economies over 2020-24—the highest share since the 1990s. Per capita income in these economies—an important indicator of living standards—is expected to grow by 3.0% on average through 2026, well below the average of 3.8% in the decade before COVID-19.

- Global inflation is expected to moderate to 3.5% in 2024 and 2.9% in 2025, but the pace of decline is slower than was projected just six months ago. Many central banks, as a result, are expected to remain cautious in lowering policy interest rates. Global interest rates are likely to remain high by the standards of recent decades—averaging about 4% over 2025-26, roughly double the 2000-19 average.

- “Although food and energy prices have moderated across the world, core inflation remains relatively high—and could stay that way,” said World Bank’s Deputy Chief Economist and Prospects Group Director Ayhan Kose. “That could prompt central banks in major advanced economies to delay interest-rate cuts. An environment of ‘higher-for-longer’ rates would mean tighter global financial conditions and much weaker growth in developing economies.”

- The latest Global Economic Prospects report also features two analytical chapters of topical importance. The first outlines how public investment can be used to accelerate private investment and promote economic growth. It finds that public investment growth in developing economies has halved since the global financial crisis, dropping to an annual average of 5% in the past decade. Yet public investment can be a powerful policy lever. For developing economies with ample fiscal space and efficient government spending practices, scaling up public investment by 1% of GDP can increase the level of output by up to 1.6% over the medium term.

- The second analytical chapter explores why small states—those with a population of around 1.5 million or less—suffer chronic fiscal difficulties. Two-fifths of the 35 developing economies that are small states are at high risk of debt distress or already in it. That’s roughly twice the share for other developing economies. Comprehensive reforms are needed to address the fiscal challenges of small states. Revenues could be drawn from a more stable and secure tax base. Spending efficiency could be improved—especially in health, education, and infrastructure. Fiscal frameworks could be adopted to manage the higher frequency of natural disasters and other shocks. Targeted and coordinated global policies can also help put these countries on a more sustainable fiscal path.World Bank says 80% of global population will experience slower growth than in pre-COVID decade | Daily FT

Tuesday, 21 May 2024

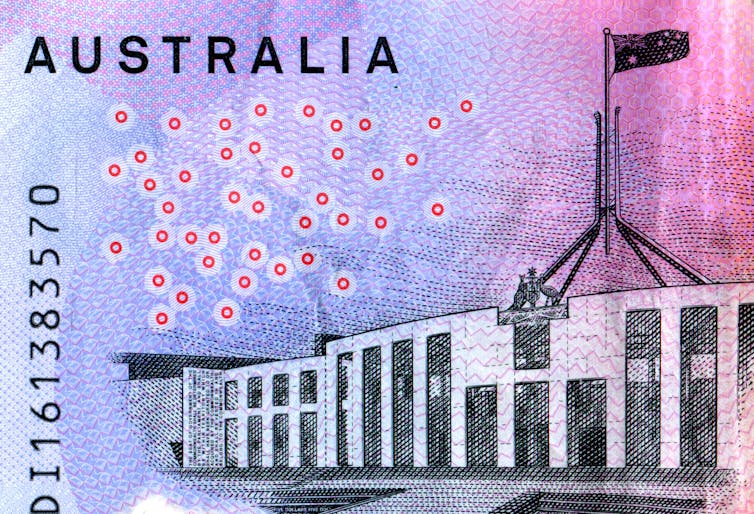

What’s the difference between fiscal and monetary policy?

This article is part two of The Conversation’s “Business Basics” series where we ask leading experts to discuss key concepts in business, economics and finance.

How governments should manage their budgets, and how interest rates should be set, are two of the most important questions in economics.

Ideally, both work hand in hand to ensure the best outcomes for the economy as a whole. But they are enacted by different branches of government, and fall into different buckets within economics.

Budgeting – the way governments tax and spend – falls within the domain of fiscal policy. In contrast, the management of credit and interest rates falls into the domain of monetary policy.

With the recent federal budget handed down amid an ongoing battle to tackle inflation, both topics have dominated recent news coverage, so it’s important to understand the difference.

Fiscal policy

Paying tax is an unavoidable fact of life, but is needed to support spending on government services such as hospitals, roads, schools and defence. Taxation and spending decisions are made on different scales at every level of government, and form the basis of a government’s fiscal policy.

Traditionally, fiscal policy was seen as a very simple equation.

Governments should spend only as much as they earn through taxation, and only take on a small amount of debt for things like longer-term infrastructure projects.

But when economic growth falls, tax revenues also fall, forcing governments to cut spending to balance their budgets. Such spending cuts come at precisely the wrong time and are only likely to further worsen economic growth.

Noticing this pattern, economist John Maynard Keynes was the first to question this traditional wisdom, arguing that fiscal policy should be “countercyclical”.

According to Keynes, when economic growth falls, government spending should increase, only falling back as the economic recovery plays out.

Under a Keynesian approach, it’s therefore wholly appropriate for governments to issue debt to fund spending increases as the economy weakens.

The problem with this view of fiscal policy is that some governments have arguably abused their licence to spend, relying on ever-increasing levels of debt.

Greece famously suffered a spectacular debt crisis after the global financial crisis in 2008, but other European countries such as France, Italy, Portugal and Spain also have high and problematic levels of debt.

Chronically high debt can lead to higher interest payments on this debt, which in turn can limit a government’s ability to spend to support its economy.

Monetary policy

Monetary policy affects the economy via a different lever.

By changing the relative cost of borrowing money, changes in interest rates affect the aggregate level of spending in the economy.

This in turn can impact inflation – increases in the general level of prices.

Cuts in interest rates will tend to stimulate demand and push prices up, while rate increases reduce demand and push prices down.

Interest rates are typically set by a country’s central bank, whose primary role is to keep inflation low.

Our own central bank – the Reserve Bank of Australia, sets rates to meet an official inflation target of between 2% and 3%.

A combined Keynesian approach

Alongside Keynes’ writing on fiscal policy, he and other economists argued that interest rates should be reduced as an economy heads into recession, to support borrowing and spending by businesses and consumers.

Coupled with higher government spending, keeping interest rates lower in a recession should theoretically speed up economic recovery.

The merits of a Keynesian approach were borne out clearly in Australia in both the 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID pandemic.

Most recently, the pandemic saw the Reserve Bank cut interest rates to almost zero. Simultaneously, the government supported the economy with a wide range of spending programs, including big boosts to welfare payments and a generous JobKeeper program to mothball Australia’s workforce.

As a result, unemployment quickly returned to low levels and economic growth recovered following the lifting of restrictions.

Helping people pay their bills while taming spending is hard

Emergence from the pandemic left us with a different problem. Inflation surged and remained stubbornly above the Reserve Bank’s target range, forcing the bank to repeatedly raise rates to try to tame it.

At the same time, the government has been trying to support Australians through a cost-of-living crisis.

Now, critics of the government have argued that further spending to support Australians could unintentionally put further pressure on inflation and force the Reserve Bank to keep interest rates higher for longer.

Such challenges reflect the fact that our understanding of best practice for fiscal and monetary policy is constantly evolving.

Problems with burgeoning state debt have prompted debate on the former, and whether there should be limits on governments’ ability to issue debt.

These could include limits to public debt, or new oversight authorities to monitor levels of public spending.

And on monetary policy, a recent review of the Reserve Bank considered requiring a “dual mandate” that would force it to give equal consideration to employment and to inflation goals, as is currently required of the US Federal Reserve.![]()

Mark Crosby, Professor, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Friday, 5 April 2024

World Bank projects India’s economy to grow at 7.5 per cent in 2024

Tuesday, 26 March 2024

French reactor using full core of recycled uranium fuel

.jpg?ext=.jpg) The Cruas-Meysse plant (Image: EDF)

The Cruas-Meysse plant (Image: EDF)Tuesday, 6 February 2024

UK decommissioning research partnership begins to bear fruit

.jpeg?ext=.jpeg)

Thursday, 11 January 2024

The BRICS are neither the anti-West nor a bloc

India’s Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman at the BRICS Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors meeting in Washington, D.C. Photo: Twitter @nirmalasitharaman retweet of April 12, 2023 from Indian Ministry of Finance

India’s Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman at the BRICS Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors meeting in Washington, D.C. Photo: Twitter @nirmalasitharaman retweet of April 12, 2023 from Indian Ministry of FinanceFriday, 10 November 2023

India’s festival season to bring some cheer to economy, say economists – Reuters Poll

Tuesday, 5 September 2023

Brazil's president proposes common currency for BRICS nations

- The President of Brazil, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, popularly known as Lula, proposed the idea of establishing a common currency among the BRICS nations.

- BRICS is a grouping of the economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. The predecessor of this group, before South Africa joined the other four in 2010 was known as BRIC.

- President Lula’s proposal aims to mitigate the susceptibility of the economies of most countries to the fluctuations in the value of the US dollar in trade and investment transactions.

- Lula put forth the suggestion on 23 August 2023 during a BRICS summit held in Johannesburg, South Africa.

- However several experts and officials have commented that there are formidable challenges associated with this initiative. Chief among them, they have said, are the significant economic, political, and geographical differences among Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

- Lula holds the view that nations not using the dollar should not be compelled to engage in trade using that currency. He expressed support for the implementation of a shared currency within the Mercosur bloc, which comprises South American countries.

- Addressing the opening session of the summit, he stated that a BRICS currency would ‘expand our payment choices and diminish our exposure to vulnerabilities.’

- South African officials had previously stated that the discussion of a BRICS currency was not included in the summit's agenda.

- Back in July, India's foreign minister, S. Jaishankar, had asserted that the concept of a BRICS currency did not exist, and the agenda would include discussions on enhancing trade in the respective national currencies.

- Russian President Vladimir Putin, who participated in the gathering via video link, said the discussions would revolve around transitioning trade between member nations from the dollar to their respective national currencies. On the other hand, China has yet to provide a statement regarding this idea.

- President Xi Jinping, during his address at the summit, emphasized the importance of advancing ‘the reform of the international financial and monetary system.’

- During an interview with a radio station in July this year, Lesetja Kganyago, governor of the South African central bank had described the creation of a BRICS currency as a ‘political endeavor’. Kganyago has emphasized the need to establish of a banking union, a fiscal union, and the attainment of macroeconomic convergence before a common BRICS currency can be created.

- A mechanism for enforcing compliance among countries is required, especially for those that deviate from the established framework. Also, the creation of a common central bank raises the question of its geographical location. Not an easy decision to reach.

- Trade imbalances pose a significant challenge, as highlighted by Herbert Poenisch, a senior fellow at Zhejiang University, in a blog post for the think-tank OMFIF.

- ‘All BRICS member nations primarily engage in trade with China, with minimal trade occurring among themselves.’

- BRICS leaders have expressed their desire to increase the use of their respective national currencies instead of relying heavily on the dollar. This shift has gained prominence, particularly after the substantial strengthening of the dollar last year due to the Federal Reserve's interest rate hikes and Russia's involvement in Ukraine, resulting in increased costs for dollar-denominated debt and imports.

- The sanctions imposed on Russia, leading to its exclusion from the global financial system last year, also heightened speculation that non-Western allies might transition away from the dollar.

- ‘In Tuesday's summit,’ Putin emphasized, ‘the relentless process of reducing our economic dependence on the dollar is gaining traction.’

- According to data from the International Monetary Fund, the dollar’s share of official foreign exchange reserves dropped to a 20-year low of 58% in the last quarter of 2022, and it fell to 47% when accounting for fluctuations in exchange rates.

- Nonetheless, the dollar continues to hold a dominant position in global trade, being involved in one side of nearly 90% of worldwide foreign exchange transactions, as reported by data from the Bank for International Settlements.De-dollarization would necessitate a widespread shift, with numerous exporters, importers, borrowers, lenders, and currency traders worldwide making independent decisions to opt for alternative currencies. Brazil's president proposes common currency for BRICS nations

Thursday, 17 August 2023

India makes rupee payments for gold and crude imports from the UAE

- By Aniket Gupta, India and the United Arab Emirates have initiated bilateral trade using their respective local currencies. The first of such transactions was the sale of 25 kg gold by a UAE bullion exporter to an Indian buyer. The deal was worth about Rs.128.4 million ($1.54 million).

- The second such bilateral transaction was in oil. Indian Oil Corporation (IOC), the country’s leading refiner, completed a rupee payment for the acquisition of one million barrels of oil from Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC).

- These transactions have been completed as part of an agreement India and the UAE signed in July 2023, which authorizes trade settlements to happen in rupees rather than US dollars. The agreement is designed to boost transaction efficiency and cut the currency conversion expense.

- During the fiscal year 2022-23, two-way trade between India and the UAE reached a total of $84.5 billion. India aims to replicate similar local currency transaction deals with other nations as a means to enhance exports amidst a lackluster global trade landscape. Currently, 1 US dollar is equivalent to 83.23 Indian rupees. Source: https://www.domain-b.com/

Wednesday, 22 March 2023

Silicon Valley Bank, sixteenth-largest US bank, collapses

Tuesday, 21 February 2023

India's consumer price inflation zooms to 6.52% in January

Wednesday, 8 February 2023

India’s diplomatic influence rose in 2022 due to leadership, says Australian think tank; China displacing India as South Asian investor

Saturday, 22 October 2022

"Diwali arrives early in Himachal...": PM Modi launches multiple projects

Friday, 14 October 2022

India pips UK to emerge world's fifth biggest economy

Wednesday, 12 October 2022

Global recession risk up in 2023 amid parallel rate hikes: World Bank

Friday, 19 February 2021

India's economic recovery is gaining steam: S&P

FEB 16, 2021 SINGAPORE: India is on track for an economic recovery in the fiscal year ending March 2022, S&P Global Ratings said on Tuesday. Consistently good agriculture performance, a flattening of the Covid-19 infection curve and a pickup in government spending are all supporting the economy, it said in a report titled 'Cross-Sector Outlook: India's Escape From Covid.' India needs many things to be right for its recovery to continue. Most significantly, the country needs to quickly and thoroughly vaccinate most of its 1.4 billion people. "The emergence of yet more contagious Covid-19 variants with the potential to evade vaccine-derived immunity present a major risk to this recovery. As does the possibility of early withdrawal of global fiscal stimulus," said the report. However, near-term prospects are positive. With a sustained decline in national confirmed Covid-19 cases allowing for a gradual relaxation of formerly stringent epidemic control measures, high frequency economic indicators continue to show improvement. S&P said the Indian government's recently released Budget will also support the recovery with higher than previously expected expenditures for fiscals 2021 and 2022. "India's improving growth prospects are critical to its ability to sustain the higher deficits associated with its more aggressive fiscal stance." The economy still faces important risks as it transitions from stabilisation to recovery. "We estimate that India faces a permanent loss of output versus its pre-pandemic path, suggesting a long-term production deficit equivalent to about 10 per cent of GDP," said the report. Localised containment measures in India are replacing nationwide lockdowns. This has rejuvenated demand and removed supply bottlenecks and labour shortages, supporting a sharp recovery in infrastructure use. But the pace of recovery varies widely. Airports are still struggling with most flights grounded. Utilities are faring better, bolstered by regulated, contracted or availability-based returns that protect their operating cash flows despite an earlier fall in unit demand. "We believe counterparty credit risks and receivable delays pose the biggest risk for utilities (including renewables) while benign funding conditions assuage liquidity risk." Likewise, a faster-than-expected earnings recovery has lowered downside risk for rated corporates. An increase in commodity prices and a revival of domestic demand after lockdowns were eased have driven upside earnings surprises. Changes in consumer choices, for example a preference for personal transport for health-safety reasons, have helped sectors like automobiles. "In our view, a sustained earnings rebound is key for ratings to stabilise. Roughly one quarter of ratings are still on negative outlook. On the other hand, proactive refinancing by speculative-grade corporates has materially reduced refinancing risk in 2021." On the banking front in India, S&P estimates the system's weak loans ratio at 12 per cent of gross loans and credit cost to remain elevated at 2.2 to 2.7 per cent. Faster economic recovery and steps taken by the Reserve Bank of India and the Indian government to cushion the effect of the economic crisis have helped ease the stress on bank balance sheets. "In our view, India's banking system's performance is likely to start improving materially in fiscal 2023, trailing an economic recovery of 10 per cent in fiscal 2022. On a positive note, banks are building capital buffers and reserves to deal with the Covid crunch." S&P said finance companies' performance has been a mixed bag and polarisation between Indian finance companies can persist. Copyright © Jammu Links News, Source: Jammu Links News

Sunday, 31 January 2021

IMF sees Indian economy growing at 11.5% in 2021

- India’s economy is expected to recover at a faster pace of 11.5 per cent in 2021, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said in its latest World Economic Outlook report, while scaling down the projected contraction in the current fiscal year. And, despite the prevailing uncertainty, IMD projects the global economy growing 5.5 per cent in 2021 and 4.2 per cent in 2022.

- The 2021 forecast is revised up 0.3 percentage point relative to the previous forecast, reflecting expectations of a vaccine-powered strengthening of activity later in the year and additional policy support in a few large economies.

- The Fund revised India's growth rate for 2021-22 to 11.5 per cent from 8.8 per cent projected in its October report, while revising outlook for the current fiscal's contraction to 8% from 10.3%.

- "The notable revisions to the forecast include the one for India (2.7 percentage points for 2021), reflecting carryover from a stronger-than-expected recovery in 2020 after lockdowns were eased," the Fund said in its report.

- The IMF's latest projection is in line with the Indian government's assessment of a strong `V’ shaped revival in the coming months, especially after the recent Covid-19 vaccine approvals.

- The vaccine approvals coupled with government measures have raised hopes of a sharp turnaround later this year.

- Earlier this month, the Indian drug regulator gave emergency use approval to vaccines by AstraZeneca and Bharat Biotech. The government has started vaccinating healthcare workers and plans to inoculate over 30 million people in the coming months.

- The IMF expects the global economy to grow 5.5 percent in 2021 and 4.2 per cent in 2022.

- “After an estimated 3.5 per cent contraction in 2020, the global economy is projected to grow 5.5 per cent in 2021 and 4.2 per cent in 2022. The estimate for 2020 is 0.9 percentage points higher than projected in the October WEO forecast. This reflects the stronger-than-expected recovery on average across regions in the second half of the year. The 2021 growth forecast is revised up 0.3 percentage points, reflecting additional policy support in a few large economies and expectations of a vaccine-powered strengthening of activity later in the year, which outweigh the drag on near-term momentum due to rising infections,” IMF stated in its report.

- The upgrade is particularly large for the advanced economy group, reflecting additional fiscal support—mostly in the United States and Japan—together with expectations of earlier widespread vaccine availability compared to the emerging market and developing economy group, it added.

- Emerging market and developing economies are also projected to trace diverging recovery paths. Considerable differentiation is expected between China — where effective containment measures, a forceful public investment response, and central bank liquidity support have facilitated a strong recovery — and other economies.

- Oil exporters and tourism-based economies within the group face particularly difficult prospects considering the expected slow normalisation of cross-border travel and the subdued outlook for oil prices. As noted in the October 2020 WEO, the pandemic is expected to reverse the progress made in poverty reduction across the past two decades. Close to 90 million people are likely to fall below the extreme poverty threshold during 2020–21.Consistent with recovery in global activity, global trade volumes are forecast to grow about 8 per cent in 2021, before moderating to 6 per cent in 2022. Services trade is expected to recover more slowly than merchandise volumes, however, which is consistent with subdued cross-border tourism and business travel until transmission declines everywhere. Source: https://www.domain-b.com/