SWNS

SWNS SWNS

SWNS SWNS

SWNS SWNS

SWNS

You probably know the feeling: you’re sitting on a plane, happily cruising through the sky, when suddenly the seat-belt light comes on and things get a little bumpy.

Most of the time, turbulence leads to nothing worse than momentary jitters or perhaps a spilled cup of coffee. In rare cases, passengers or flight attendants might end up with some injuries.

What’s going on here? Why are flights usually so stable, but sometimes get so unsteady?

As a meteorologist and atmospheric scientist who studies air turbulence, let me explain.

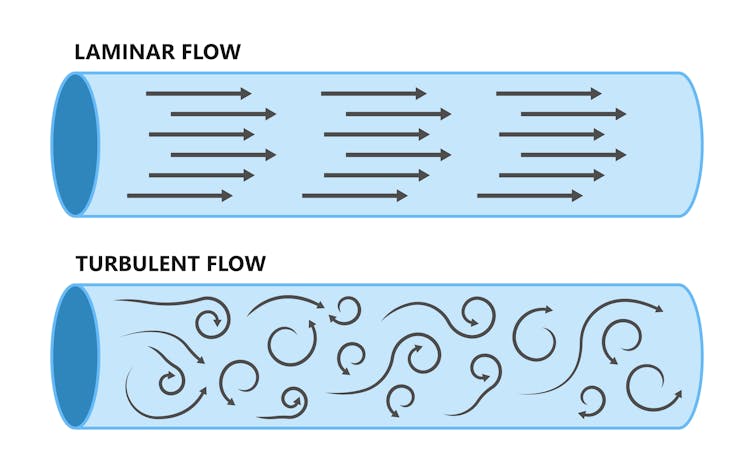

Air turbulence is when the air starts to flow in a chaotic or random way.

At high altitudes the wind usually moves in a smooth, horizontal current called “laminar flow”. This provides ideal conditions for steady flight.

In ‘laminar flow’, air moves smoothly in one direction. When turbulence begins, it goes every which way. Shutterstock

In ‘laminar flow’, air moves smoothly in one direction. When turbulence begins, it goes every which way. ShutterstockTurbulence occurs when something disrupts this smooth flow, and the air starts to move up and down as well as horizontally. When this happens, conditions can change from moment to moment and place to place.

You can think of normal flying conditions as the glassy surface of the ocean on a still day. But when a wind comes up, things get choppy, or waves form and break – that’s turbulence.

The kind of turbulence that affects commercial passenger flights has three main causes.

The first is thunderstorms. Inside a thunderstorm, there is strong up-and-down air movement, which makes a lot of turbulence that can spread out to the surrounding region. Thunderstorms can also create “atmospheric waves”, which travel through the surrounding air and eventually break, causing turbulence.

Fortunately, pilots can usually see thunderstorms ahead (either with the naked eye or on radar) and will make efforts to go around them.

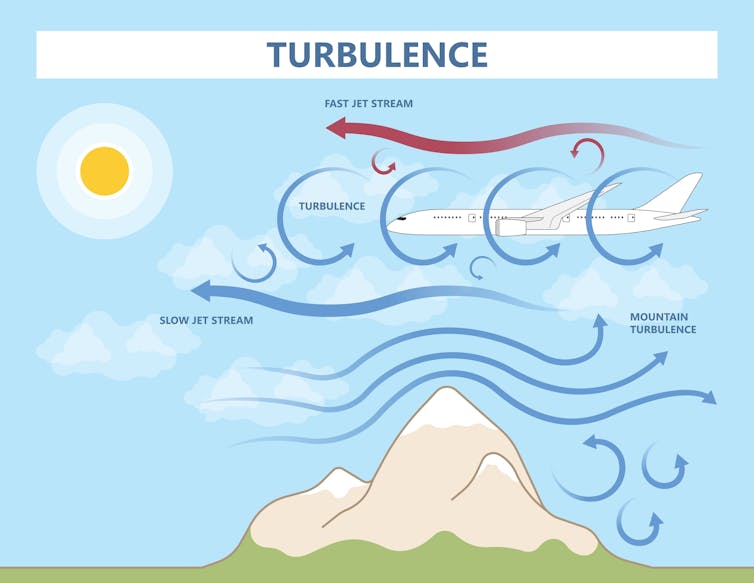

The other common causes of turbulence create what’s typically called “clear-air turbulence”. It comes out of air that looks perfectly clear, with no clouds, so it’s harder to dodge.

Jet streams and mountains are common causes of clear-air turbulence. Shutterstock

Jet streams and mountains are common causes of clear-air turbulence. ShutterstockThe second cause of turbulence is jet streams. These are high-speed winds in the upper atmosphere, at the kind of altitudes where passenger jets fly.

While air inside the jet stream moves quite smoothly, there is often turbulence near the top and bottom of the stream. That’s because there is a big difference in air speed (called “wind shear”) between the jet stream and the air outside it. High levels of wind shear create turbulence.

The third thing that makes turbulence is mountains. As air flows over a mountain range, it creates another kind of wave – called, of course, a “mountain wave” – that disrupts air flow and can create turbulence.

Pilots do their best to avoid air turbulence – and they’re pretty good at it!

As mentioned, thunderstorms are the easiest to fly around. For clear-air turbulence, things are a little trickier.

When pilots encounter turbulence, they will change altitude to try to avoid it. They also report the turbulence to air traffic controllers, who pass the information on to other flights in the area so they can try to avoid it.

Weather forecasting centres also provide turbulence forecasts. Based on their models of what’s happening in the atmosphere, they can predict where and when clear-air turbulence is likely to occur.

As the globe warms and the climate changes in coming decades, we think air turbulence will also be affected.

One reason is that the jet streams which can cause turbulence are shifting and may become more intense. As Earth’s tropical climate zones spread away from the equator, the jet streams are moving with them.

This is likely to increase turbulence on at least some flight routes. Some studies also suggest the wind shear around jet streams has become more intense.

Another reason is that the most severe thunderstorms are also likely to become more intense, partly because a warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapour. This too is likely to generate more intense turbulence.

These predictions are largely based on climate models, because it is difficult to collect the data needed to identify trends in air turbulence. These data largely come from reports by aircraft, the quality and extent of which are changing over time. These measurements are quite different from the long-term, methodically gathered data usually used to detect trends in the weather and climate.

Around the globe, air turbulence causes hundreds of injuries each year among passengers and flight attendants on commercial aircraft. But, given the hundreds of millions of people who fly each year, those are pretty good odds.

Turbulence is usually short-lived. What’s more, modern aircraft are engineered to comfortably withstand all but the most extreme air turbulence.

And among people who are injured, the great majority are those who aren’t strapped in. So if you’re concerned, the easiest way to protect yourself is to wear your seat belt. ![]()

Todd Lane, Professor, School of Geography, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, The University of Melbourne, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

With the coalition government’s ban of student mobile phones in New Zealand schools coming into effect this week, reaction has ranged from the sceptical (kids will just get sneakier) to the optimistic (most kids seem okay with it).

In a world where nearly everyone has a smartphone, it’s to be expected nearly everyone will have an opinion. The trick is to sort the valid from the kneejerk, and not rush to judgement.

Anecdotally, schools that implemented the ban ahead of the deadline have reported positive changes in attention and learning. The head girl of Hornby High School in Christchurch said the grounds are now “almost louder during intervals and lunches”. Her principal said, “I wish we had done the phone ban five years ago.”

On the other hand, hard evidence in favour of banning phones in schools has been found to be “weak and inconclusive”. But the policy’s aim to create a “positive environment where young New Zealanders can focus on what matters most” is not without merit.

Above all, the policy raises a crucial question: is an outright ban the most effective approach to addressing the problem of digital distraction and its impact on education?

Since Monday, students have had to store their phones in bags or lockers during school hours. As in the pre-digital era, parents can now only contact their children through the school office.

The aim, according to the National Party’s original election promise, is to “eliminate unnecessary disturbances or distractions” and improve student achievement, which by various measures has declined over the past three decades.

While avoiding generalised assumptions, we know many young people can’t put their devices down, as both a recent Education Review Office report and a 2021 OECD survey concluded.

In one US survey in 2022, approximately one-third of teachers asked students to put away their phones five to ten times per class, while nearly 15% asked more than 20 times.

So, it’s hard to argue phones aren’t a distraction, or that social media-fuelled bullying and isolation don’t warrant critical examination of digital habits. At the same time, phones have their constructive uses, from organising schedules for the neurodivergent, to facilitating social interactions and learning.

No phone ban advocate is arguing that limiting phone use in schools is a silver bullet for related issues around cyberbullying, mental health and behavioural challenges. But the personal device’s capacity to distract remains a legitimate concern.

The digital classroom presents challenges to developing critical thinking skills. Getty Images

The digital classroom presents challenges to developing critical thinking skills. Getty ImagesThe heart of the debate lies in education’s evolving landscape. The push to ban phones does not extend to digital devices in general, after all. Their utility in learning environments is well recognised.

But as we embrace artificial intelligence and other technological advances in education, we must also ask: at what point does reliance on these digital tools begin to erode critical thinking skills?

The future job market, filled with roles that do not yet exist, will undoubtedly require those skills. Therefore, distinguishing between meaningful digital engagement and detrimental distraction is crucial.

Perhaps the better question is: would fewer distractions create the opportunity for young people to be more curious about their learning?

Curiosity is essential for educational success, citizenship and media literacy in the digital age. But curiosity is stifled by distractions.

Education research is heading towards treating curiosity as a “provocation” – meaning we should, in effect, “dare” young people to be more curious. This involves encouraging mistakes, exploration – even daydreaming or being creatively bored.

All of this is challenging with the current level of distractions in the classroom. On top of that, many young people struggle to cultivate curiosity when digital media can provide instant answers.

Consider the distinction between two types of curiosity: “interest curiosity” and what has been termed “deprivation curiosity”.

Interest curiosity is a mindful process that tolerates ambiguity and takes the learner on their own journey. It’s a major characteristic of critical thinking, particularly vital in a world where AI systems are competing for jobs.

Deprivation curiosity, by contrast, is characterised by impulsivity and seeking immediate answers. Misinformation and confusion fuelled by AI and digital media only exacerbate the problem.

Where does this leave the phone ban in New Zealand schools? There are some promising signs from students themselves, including in the OECD’s 2022 report on global educational performance:

On average across OECD countries, students were less likely to report getting distracted using digital devices when the use of cell phones on school premises is banned.

These early indications suggest phone bans boost the less quantifiable “soft” skills and vital developmental habits of young people — social interactions, experimentation, making mistakes and laughing. These all enhance the learning environment.

Real life experiences, with their inherent trials and errors, are irreplaceable avenues for applying critical thinking. Digital experiences, while valuable, cannot fully replicate the depth of human interaction and learning.

Finding the balance is the current challenge. As a 2023 UNESCO report advised, “some technology can support some learning in some contexts, but not when it is over-used”.

In the meantime, we should all remain curious about the potential positive impacts of the phone ban policy, and allow time for educators and students to respond properly. The real tragedy would be to miss the learning opportunities afforded by a less distracted student population.![]()

Patrick Usmar, Lecturer in Critical Media Literacies, Auckland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This article is part two of The Conversation’s “Business Basics” series where we ask leading experts to discuss key concepts in business, economics and finance.

How governments should manage their budgets, and how interest rates should be set, are two of the most important questions in economics.

Ideally, both work hand in hand to ensure the best outcomes for the economy as a whole. But they are enacted by different branches of government, and fall into different buckets within economics.

Budgeting – the way governments tax and spend – falls within the domain of fiscal policy. In contrast, the management of credit and interest rates falls into the domain of monetary policy.

With the recent federal budget handed down amid an ongoing battle to tackle inflation, both topics have dominated recent news coverage, so it’s important to understand the difference.

Paying tax is an unavoidable fact of life, but is needed to support spending on government services such as hospitals, roads, schools and defence. Taxation and spending decisions are made on different scales at every level of government, and form the basis of a government’s fiscal policy.

Traditionally, fiscal policy was seen as a very simple equation.

Governments should spend only as much as they earn through taxation, and only take on a small amount of debt for things like longer-term infrastructure projects.

But when economic growth falls, tax revenues also fall, forcing governments to cut spending to balance their budgets. Such spending cuts come at precisely the wrong time and are only likely to further worsen economic growth.

Noticing this pattern, economist John Maynard Keynes was the first to question this traditional wisdom, arguing that fiscal policy should be “countercyclical”.

According to Keynes, when economic growth falls, government spending should increase, only falling back as the economic recovery plays out.

Under a Keynesian approach, it’s therefore wholly appropriate for governments to issue debt to fund spending increases as the economy weakens.

The problem with this view of fiscal policy is that some governments have arguably abused their licence to spend, relying on ever-increasing levels of debt.

Greece famously suffered a spectacular debt crisis after the global financial crisis in 2008, but other European countries such as France, Italy, Portugal and Spain also have high and problematic levels of debt.

Chronically high debt can lead to higher interest payments on this debt, which in turn can limit a government’s ability to spend to support its economy.

Monetary policy affects the economy via a different lever.

By changing the relative cost of borrowing money, changes in interest rates affect the aggregate level of spending in the economy.

This in turn can impact inflation – increases in the general level of prices.

Cuts in interest rates will tend to stimulate demand and push prices up, while rate increases reduce demand and push prices down.

Interest rates are typically set by a country’s central bank, whose primary role is to keep inflation low.

Our own central bank – the Reserve Bank of Australia, sets rates to meet an official inflation target of between 2% and 3%.

Alongside Keynes’ writing on fiscal policy, he and other economists argued that interest rates should be reduced as an economy heads into recession, to support borrowing and spending by businesses and consumers.

Coupled with higher government spending, keeping interest rates lower in a recession should theoretically speed up economic recovery.

The merits of a Keynesian approach were borne out clearly in Australia in both the 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID pandemic.

Most recently, the pandemic saw the Reserve Bank cut interest rates to almost zero. Simultaneously, the government supported the economy with a wide range of spending programs, including big boosts to welfare payments and a generous JobKeeper program to mothball Australia’s workforce.

As a result, unemployment quickly returned to low levels and economic growth recovered following the lifting of restrictions.

Emergence from the pandemic left us with a different problem. Inflation surged and remained stubbornly above the Reserve Bank’s target range, forcing the bank to repeatedly raise rates to try to tame it.

At the same time, the government has been trying to support Australians through a cost-of-living crisis.

Now, critics of the government have argued that further spending to support Australians could unintentionally put further pressure on inflation and force the Reserve Bank to keep interest rates higher for longer.

Such challenges reflect the fact that our understanding of best practice for fiscal and monetary policy is constantly evolving.

Problems with burgeoning state debt have prompted debate on the former, and whether there should be limits on governments’ ability to issue debt.

These could include limits to public debt, or new oversight authorities to monitor levels of public spending.

And on monetary policy, a recent review of the Reserve Bank considered requiring a “dual mandate” that would force it to give equal consideration to employment and to inflation goals, as is currently required of the US Federal Reserve.![]()

Mark Crosby, Professor, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Antonio Guillem/Shutterstock Timothy Colin Bednall, Swinburne University of TechnologyWith the new year underway employers are beginning to resume normal business activities and restart their hiring process. Similarly, many school and university graduates are beginning their job search after a well-earned break.

Antonio Guillem/Shutterstock Timothy Colin Bednall, Swinburne University of TechnologyWith the new year underway employers are beginning to resume normal business activities and restart their hiring process. Similarly, many school and university graduates are beginning their job search after a well-earned break.

While some employers are using increasingly sophisticated approaches to recruiting such as psychometric testing and artificial intelligence, interviews remain one of the most common selection methods.

If you have been invited to a job interview, congratulations, as it likely means you have been shortlisted for the role. However, for many people, interviews can be an unnerving process. Not only do they require candidates to think on their feet, but also to create a positive impression of themselves as a potential co-worker.

With that in mind, it always pays to prepare by anticipating what will be discussed and practising your answers. Here are six types of questions you may be asked:

An interview will often start with broad questions about your background and interest in a job. These may include questions such as: “What motivated you to apply for this role?” or “Tell me about your long-term career aspirations”.

For these types of questions, a convincing answer will highlight relevant skills you can bring to the role. These professional experiences do not have to come from the same type of position. For instance, if you were applying for a customer service job, you might cite communication and problem-solving methods you used on a student team project.

Interview candidates need to present themselves as someone others would want to work with. fizkes/Shutterstock

Interview candidates need to present themselves as someone others would want to work with. fizkes/ShutterstockA convincing answer will focus on intrinsic motivation: specifically, the aspects of the job you find interesting, enjoyable or otherwise rewarding. These could involve working with people, solving tricky business problems or making a social impact. Avoid negative remarks about your current employer and sources of extrinsic motivation - such as money or benefits - unless part of a salary negotiation.

Your answer will also show how the role aligns with your own values. For instance, if you are applying for a teaching position, you could highlight your belief in the importance of education, as well as anything about the school you admire, such as its program of extracurricular activities.

Behavioural questions require candidates to provide examples of the past actions they took to manage situations. For instance: “Tell me about a time when you received a customer complaint. What actions did you take, and what was the outcome?” Their objective is to predict how candidates will behave in similar situations.

You can prepare for these questions by studying the job selection criteria and anticipating the questions the interviewer may ask.

If you do not have the relevant experience for one of the questions, you can say that you can’t recall a specific example, but you could outline how you would deal with the situation described in the question.

Interviewers will often ask about what you see as your greatest strengths and weaknesses.

The strengths part of this question enables you to highlight your knowledge and skills most relevant for the role. In general, it is a good idea to provide examples of specific accomplishments that illustrate these capabilities.

The weaknesses can be addressed by framing “weaknesses” as professional aspirations. In general, it is a good idea to focus on a capability that is non-essential for the role, in which you would like to gain experience. For instance, if you are not a confident public speaker but recognise it as a necessary for your long-term career, you could say it is a skill you would like to work on.

Weaknesses, such as a lack of public speaking experience, should be framed as professional aspirations. Mentatdgt/Shutterstock

Weaknesses, such as a lack of public speaking experience, should be framed as professional aspirations. Mentatdgt/ShutterstockBy expressing willingness to receive further training and development, you can leave a much more positive impression than simply listing your current shortcomings.

Usually, pay negotiations will occur after an offer has been made, but sometimes the topic will come up during the interview.

Before stating your expectation, it is wise to find out the salary and other benefits associated with the role. If the salary has not been listed in the job description, you should ask the employer what the budgeted salary range for the position is.

Ahead of the interview, do some research and find out what is typical for the role you are applying for based on your level of experience.

Be careful about disclosing your current salary; this information can provide a baseline that can make it difficult to negotiate a higher salary. If you are asked this question, you can politely decline to answer or indicate the information is between yourself and your current employer.

Unfortunately, some employers may ask inappropriate or illegal questions. These may relate to relationship status, carer responsibilities, childhood planning, physical or mental health, cultural or ethnic background and union activity.

If you are asked an inappropriate question, you can politely ask the interviewer how that information would be relevant to your ability to perform the job.

Ultimately, job candidates have a right to refuse to answer such questions, and employers who ask them may open themselves to legal action through the Fair Work Commission, Fair Work Ombudsman or the Australian Human Rights Commission.

Often, the interviewer will invite the candidate to ask their own questions. Thoughtfully selected questions can leave a positive lasting impression.

In this part of the interview, you can clarify any aspect of the role you feel unsure about, such as the working hours. It can also be good to do some research on the organisation and to ask some more specific questions about its clients, projects, or long-term plans.

Beyond the specific requirements of the role, a good topic to ask about is the team and organisational culture. You could, for example, ask what a typical day in the life of a team member would look like.

At the end of the interview, you should ask about the next steps including when you should expect to hear back from them.

One final thing to consider about an interview is that it is a two-way process; you are also interviewing the employer to see if the job would be a good fit for you personally and professionally. If the role, organisation or people seem unappealing after the interview process, then it is wise to look elsewhere.![]()

Timothy Colin Bednall, Associate Professor in Management, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Some animals, including goats, regularly give birth to two babies at once. Image Source via Getty Images

Some animals, including goats, regularly give birth to two babies at once. Image Source via Getty ImagesWe are faculty members at Mississippi State University College of Veterinary Medicine. We’ve been present for the births of many puppies and kittens over the years – and the animal moms almost always deliver multiples.

But are all those animal siblings who share the same birthday twins?

Twins are defined as two offspring from the same pregnancy.

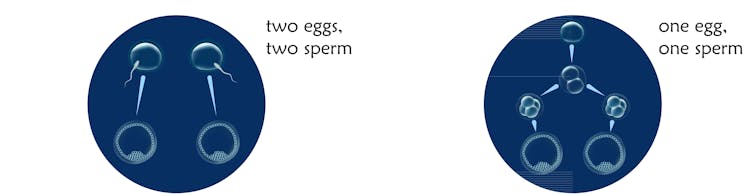

They can be identical, which means a single sperm fertilized a single egg that divided into two separate cells that went on to develop into two identical babies. They share the same DNA, and that’s why the two twins are essentially indistinguishable from each other.

Twins can also be fraternal. That’s the outcome when two separate eggs are fertilized individually at the same time. Each twin has its own set of genes from the mother and the father. One can be male and one can be female. Fraternal twins are basically as similar as any set of siblings.

Fraternal twins originate in two eggs fertilized separately, while identical twins originate in a single fertilized egg that divides to create two embryos. Veronika Zakharova/Science Photo Library via Getty Images

Fraternal twins originate in two eggs fertilized separately, while identical twins originate in a single fertilized egg that divides to create two embryos. Veronika Zakharova/Science Photo Library via Getty ImagesApproximately 3% of human pregnancies in the United States produce twins. Most of those are fraternal – approximately one out of every three pairs of twins is identical.

Each kind of animal has its own standard number of offspring per birth. People tend to know the most about domesticated species that are kept as pets or farm animals.

One study that surveyed the size of over 10,000 litters among purebred dogs found that the average number of puppies varied by the size of the dog breed. Miniature breed dogs – like chihuahuas and toy poodles, generally weighing less than 10 pounds (4.5 kilograms) – averaged 3.5 puppies per litter. Giant breed dogs – like mastiffs and Great Danes, typically over 100 pounds (45 kilograms) – averaged more than seven puppies per litter.

When a litter of dogs, for instance, consists of only two offspring, people tend to refer to the two puppies as twins. Twins are the most common pregnancy outcome in goats, though mom goats can give birth to a single-born kid or larger litters, too. Sheep frequently have twins, but single-born lambs are more common.

Horses, which are pregnant for 11 to 12 months, and cows, which are pregnant for nine to 10 months, tend to have just one foal or calf at a time – but twins may occur. Veterinarians and ranchers have long believed that it would be financially beneficial to encourage the conception of twins in dairy and beef cattle. Basically the farmer would get two calves for the price of one pregnancy.

But twins in cattle may result in birth complications for the cow and undersized calves with reduced survival rates. Similar risks come with twin pregnancies in horses, which tend to lead to both pregnancy complications that may harm the mare and the birth of weak foals.

So plenty of animals can give birth to twins. A more complicated question is whether two animal babies born together are identical or fraternal twins.

Biologists believe that identical twins in most animals are very rare. The tricky part is that lots of animal siblings look very, very similar and researchers need to do a DNA test to confirm whether two animals do in fact share all their genes. Only one documented report of identical twin dogs was confirmed by DNA testing. But no one knows for sure how frequently fertilized animal eggs split and grow into identical twin animal babies.

And reproduction is different in various animals. For instance, nine-banded armadillos normally give birth to identical quadruplets. After a mother armadillo releases an egg and it becomes fertilized, it splits into four separate identical cells that develop into identical pups. Its relative, the seven-banded armadillo, can give birth to anywhere from seven to nine identical pups at one time.

There’s still a lot that scientists aren’t sure about when it comes to twins in other species. Since DNA testing is not commonly performed in animals, no one really knows how often identical twins are born. It’s possible – maybe even likely – that identical twins may have been born in some species without anyone’s ever knowing.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Michael Jaffe, Associate Professor of Small Animal Surgery, Mississippi State University and Tracy Jaffe, Assistant Clinical Professor of Veterinary Medicine, Mississippi State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shutterstock

Melinda Jackson, Monash University and Hailey Meaklim, The University of Melbourne

Shutterstock

Melinda Jackson, Monash University and Hailey Meaklim, The University of MelbourneYou’re lying in bed, trying to fall asleep but the racing thoughts won’t stop. Instead, your brain is busy making detailed plans for the next day, replaying embarrassing moments (“why did I say that?”), or producing seemingly random thoughts (“where is my birth certificate?”).

Many social media users have shared videos on how to fall asleep faster by conjuring up “fake scenarios”, such as a romance storyline where you’re the main character.

But what does the research say? Does what we think about before bed influence how we sleep?

It turns out people who sleep well and those who sleep poorly have different kinds of thoughts before bed.

Good sleepers report experiencing mostly visual sensory images as they drift to sleep – seeing people and objects, and having dream-like experiences.

They may have less ordered thoughts and more hallucinatory experiences, such as imagining you’re participating in events in the real world.

For people with insomnia, pre-sleep thoughts tend to be less visual and more focused on planning and problem-solving. These thoughts are also generally more unpleasant and less random than those of good sleepers.

People with insomnia are also more likely to stress about sleep as they’re trying to sleep, leading to a vicious cycle; putting effort into sleep actually wakes you up more.

People with insomnia often report worrying, planning, or thinking about important things at bedtime, or focusing on problems or noises in the environment and having a general preoccupation with not sleeping.

Unfortunately, all this pre-sleep mental activity can prevent you drifting off.

One study found even people who are normally good sleepers can have sleep problems if they’re stressed about something at bedtime (such as the prospect of having to give a speech when they wake up). Even moderate levels of stress at bedtime could affect sleep that night.

Another study of 400 young adults looked at how binge viewing might affect sleep. The researchers found higher levels of binge viewing were associated with poorer sleep quality, more fatigue, and increased insomnia symptoms. “Cognitive arousal”, or mental activation, caused by an interesting narrative and identifying with characters, could play a role.

Cognitive refocusing, developed by US psychology researcher Les Gellis, involves distracting yourself with pleasant thoughts before bed. It’s like the “fake scenarios” social media users post about – but the trick is to think of a scenario that’s not too interesting.

Decide before you go to bed what you’ll focus on as you lie there waiting for sleep to come.

Pick an engaging cognitive task with enough scope and breadth to maintain your interest and attention – without causing emotional or physical arousal. So, nothing too scary, thrilling or stressful.

For example, if you like interior decorating, you might imagine redesigning a room in your house.

If you’re a football fan, you might mentally replay a passage of play or imagine a game plan.

A music fan might mentally recite lyrics from their favourite album. A knitter might imagine knitting a blanket.

Whatever you choose, make sure it’s suited to you and your interests. The task needs to feel pleasant, without being overstimulating.

Cognitive refocusing is not a silver bullet, but it can help.

One study of people with insomnia found those who tried cognitive refocusing had significant improvements in insomnia symptoms compared to a control group.

Another age-old technique is mindfulness meditation.

Meditation practice can increase our self-awareness and make us more aware of our thoughts. This can be useful for helping with rumination; often when we try to block or stop thoughts, it can make matters worse.

Mindfulness training can help us recognise when we’re getting into a rumination spiral and allow us to sit back, almost like a passive observer.

Try just watching the thoughts, without judgement. You might even like to say “hello” to your thoughts and just let them come and go. Allow them to be there and see them for what they are: just thoughts, nothing more.

Good sleep starts the moment you wake up. To give yourself your best shot at a good night’s sleep, start by getting up at the same time each day and getting some morning light exposure (regardless of how much sleep you had the night before).

Have a consistent bedtime, reduce technology use in the evening, and do regular exercise during the day.

If your mind is busy at bedtime, try cognitive refocusing. Pick a “fake scenario” that will hold your attention but not be too scary or exciting. Rehearse this scenario in your mind at bedtime and enjoy the experience.

You might also like to try:

keeping a consistent bedtime routine, so your brain can wind down

writing down worries earlier in the day (so you don’t think about them at bedtime)

adopting a more self-compassionate mindset (don’t beat yourself up at bedtime over your imagined shortcomings!).![]()

Melinda Jackson, Associate Professor at Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health, School of Psychological Sciences, Monash University and Hailey Meaklim, Sleep Psychologist and Researcher, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.