_20628.jpg)

Tuesday, 18 March 2025

EU funding for French enrichment plant expansion

_20628.jpg)

Wednesday, 11 December 2024

Frenchman sails around the world in 80 days... on dry land

Friday, 8 November 2024

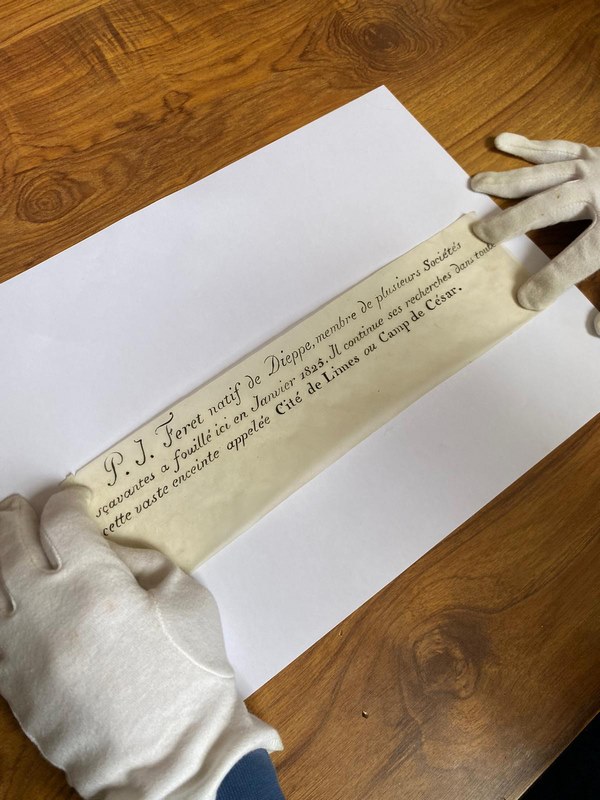

Researchers Discover 200-year-old Message in a Bottle: A ‘Magic Moment’

credit – Guillaume Blondel, Archaeological Service of the City of Eu

credit – Guillaume Blondel, Archaeological Service of the City of Eu

Sunday, 3 November 2024

Where in the world is closest to becoming a '15-minute city' ?

Monday, 16 September 2024

Paris Paralympics 2024 concludes with closing ceremony in French capital

Tuesday, 2 July 2024

How the Paris Olympics could become a super-spreader event for dengue

In September 2023, several people came down with dengue fever in Paris, France. The presence of this mosquito-borne disease was notable for two reasons. It was the most northerly outbreak ever recorded, and none of the people had travelled recently. This demonstrated it is now possible for dengue to be transmitted locally in northern Europe.

These facts are important in 2024 because of the Olympics. France waits in anticipation of more than 10 million athletes, spectators, officials and tourists descending on the city for the event. The French government knows there is a risk of dengue. In Paris, hundreds of sites are being regularly checked for the presence of the dengue-carrying mosquitoes. Will this be enough?

The concept of the super-spreader in infection epidemiology is not new. In essence, it means that a small fraction of a population, maybe just one person, is responsible for most of the cases. A famous historical super-spreader was “typhoid Mary”. Mary Mallon was an asymptomatic carrier of typhoid who may have infected over 100 people.

A study published in the journal Nature suggests that about 15% of people were responsible for 85% of cases of COVID in Hunan Province, China. In terms of dengue, one analysis from Peru of super-spreading suggests 8% of human-occupied spaces are responsible for over half of cases. (It should be noted that dengue cannot be caught directly from another human, only from the bite of a dengue-carrying mosquito.)

This is not the first time the Olympics has been identified as a risk factor for viral epidemics. The 2016 Olympics in Brazil were almost postponed because of fears about Zika - another virus transmitted by the Aedes mosquito.

In the end, any worries were put to bed, because there were no reported cases.

Fear about COVID spreading via the Tokyo Olympics brought about drastic measures to limit transmission. At that event, few infections occurred inside the Olympic bubble, but there was an increase in cases among the general population.

So what is different about Paris?

Aedes has spread considerably further than in 2016, and the number of dengue cases worldwide has increased dramatically in the same period. In 2016 there were 5.2 million cases reported worldwide. Halfway through 2024, there have already been 7.6 million cases.

Visitors from more than 200 countries are expected in France for the Olympics. Many of those countries are already experiencing dengue this year.

For the Paris Olympics to become a super-spreader event, several factors must overlap. There needs to be enough mosquitoes, enough susceptible and already-infected people, enough time and enough mosquito bites.

Perfectly adapted

The tiger mosquito is perfectly adapted to the urban Paris environment. It needs just the smallest amount of water in a small container to lay its eggs. It preferentially feeds on humans, at dawn and dusk. The eggs themselves can withstand dry conditions for months. Once wet again, the eggs will hatch.

What makes this situation potentially dangerous for Paris is that some of these mosquitoes may have dengue already inside them, passed down from their mother. This could significantly reduce the number of bites needed to start an epidemic.

Within the time frame of the Olympics, an infected athlete or spectator could be bitten once by a mosquito and seed an epidemic in a week or so. Each female mosquito can lay up to 200 eggs at a time.

Most dengue cases are asymptomatic. People infected before or during the Olympics may have no idea they are carrying the virus. They might take the virus back home and seed an epidemic there without ever knowing it.

Whether people get sick or not, they are carrying the virus and can transmit the infection onwards if they get bitten by an Aedes mosquito.

At the Rio Carnival this year, a dengue outbreak just days before the event led to a public health emergency being called, but the event wasn’t cancelled.

There will be no public health emergency in Paris because the event itself is the risk factor. Anyone living, working, visiting, competing, volunteering or even just passing through Paris during the Olympic period is going to be part of a huge natural experiment – whether they know it or not.![]()

Mark Booth, Senior Lecturer in Parasite Epidemiology, School of Natural and Environmental Sciences, Newcastle University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Friday, 26 April 2024

How breakdancing became the latest Olympic sport

“Breaking” is the only new sport making its debut at the Paris 2024 Olympics. Breaking is probably better known to most of us as breakdancing. So why is the sport officially called breaking, and how is something so freestyle and subjective going to play out as a scored sport in Paris this summer?

The origins of breaking are somewhat debatable, although most agree its roots can be traced to 1970s house parties in the Bronx area of New York hosted by DJ Kool Herc, the founder of hip-hop. Breaking was performed on the dance floor by so-called B-boys and B-girls when the music tracks were “breaking” – meaning all that could be heard was the percussion track.

Throughout the 1980s the phenomenon garnered international exposure via music videos and movies such as Flashdance (1983), Breakin’ (1984) and Beat Street (1984). This is also when the media started to use the term “breakdancing”. However, breakers never add “dance” on the end, as this term came from outsiders rather than the hip-hop community, as one of the breaking pioneers Crazy Legs has pointed out.

While the idea of testing each other in format-free “cyphers” (when people gather in a circle and somebody freestyles in the middle) has always been fundamental to breakers, the importance and the number of organised breaking competitions has steadily grown with commercialisation and codification of the activity.

There have always been two main formats: crew competitions and one-on-one solo battles, which have manifested the individualism, creativity and self-expression of breakers. Still, as with many alternative activities evolving into sports, like skateboarding or surfing, the governance and competition frameworks have remained fragmented until recently.

It was not until 2018 that breaking became officially governed by the World DanceSport Federation. However, major competitions still exist outside the official governance, such as Red Bull BC One and the Battle of the Year, that arguably carry more credibility within the breaking community.

Why the Olympics?

Since the Olympic Agenda 2020 – a road map for the Olympic movement based on the three pillars of credibility, sustainability and youth – the IOC has continued to modernise the Olympic programme to make it more attractive to a wider and younger audience.

Undoubtedly, the inclusion of breaking fits well with that overall strategy – there has been nothing similar to breaking on the programme in terms of its creativity, affordability (no tools or equipment needed) and its urban nature. It is also fair to say though that breaking made it to Paris 2024 thanks to the insistence of the host country.

Apart from the usual core Olympic programme, the host country of each Olympics has five additional slots that they can fill with the sports of their preference. I analysed the Tokyo 2020 Games to find that when it came to its medal tally, Japan benefited from local favourites like karate, skateboarding, baseball and softball.

Los Angeles 2028 will add flag football (a variant of American football), lacrosse, cricket and squash. Bizarrely, Paris 2024 may well be the only time we will see breaking in the Olympics in the foreseeable future, although the World DanceSport Federation (WDSF) is determined to ensure it returns in Brisbane 2032.

What we will see in Paris?

There are a lot of odd new terms to learn if you have never watched a breaking contest, such as “turtle freeze”, “six-steps” and “coin drop”. However, the format of Olympic competition is very straightforward: 16 B-boys and 16 B-girls will battle it out head-to-head under the lights of the Place de la Concorde.

There is a three-part qualifier for the games, so no doubt each of those qualifying athletes will be in the history books. Already qualified through WDSF World and continental championships are some heavy favourites, such as B-boys Victor (US) and Danny Dan (France), and B-girls India (Netherlands) and Nicka (Lithuania).

The last 14 will be decided by the top-ranked 80 breakers at the dedicated Olympic qualifier series in Shanghai in May and Budapest in June. To make the competition diverse, the IOC has limited each country to a maximum of two B-boys and two B-girls, while introducing two universal places that provide opportunities to smaller and emerging nations.

As in any creative sport, there are inevitable questions about scoring in breaking. Indeed, there is always going to be a substantial degree of subjectivity, but not drastically more than in established Olympic sports like gymnastics, synchronised swimming or figure skating.

Traditionally, three or five judges have been used in major breaking contests. However, this number has increased to nine in the Olympic framework, presumably to minimise subjectivity and risk of errors.

The trivium judging system that will be used in Paris was developed by influential B-boy Storm and DJ Renegade for the 2018 Youth Olympics, and has been fine-tuned through the series of WDSF events since.

It is based on six criteria to decide the winner of each battle: creativity, personality, technique, variety, performativity and musicality – this means connecting to a musical track that is not known in advance.

The breaking community has always been very close and informal, and some breakers and judges might find the new formalities of sporting frameworks unusual. However, there is still one unique feature that will hopefully survive the formalisation – it is the only sport where the judges have to perform for the athletes and spectators.

This usually happens before the competition starts and is called “the judges’ showcase”. University lecturer Rachael Gunn, aka B-girl Raygun, (who won the Oceania Breaking Championships and qualified for the Olympics) sees this unique practice as a symbolic gesture, a demonstration that underscores the unity and shared passion between contestants and those judging them.

So don’t forget to tune in early on August 9 and 10 to witness this special celebration before following this exciting contest when we will see the first-ever Olympic breaking champions crowned.

Mikhail Batuev, Lecturer in Sport Management, Department of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation, Northumbria University, Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tuesday, 26 March 2024

French reactor using full core of recycled uranium fuel

.jpg?ext=.jpg) The Cruas-Meysse plant (Image: EDF)

The Cruas-Meysse plant (Image: EDF)Monday, 18 March 2024

Women in the UK miss out on 1 million pay rises

Wednesday, 13 March 2024

What is this thing called love?

Researchers are divided about the nature of love, and whether it is universal or changeable. Shutterstock

Sarah Pinto, Deakin University

Researchers are divided about the nature of love, and whether it is universal or changeable. Shutterstock

Sarah Pinto, Deakin UniversityLove it or loathe it, Valentine’s Day is a celebration of romantic love. But what exactly is romantic love? Researchers are increasingly interested in this question, and the answer is not at all clear.

What is an emotion?

Everyone from Plato to Taylor Swift has pondered the meaning of love. But, in the last two decades, researchers in the humanities and across the social, behavioural and cognitive sciences have also investigated romantic love.

Most – though not all – researchers are happy to call romantic love a human emotion. But what researchers mean by “emotion” varies.

Some explain emotions as hard-wired biological processes that are innate to humans. Others talk about them as behaviours or experiences that involve cognitive judgements. And still others think emotions are socially constructed, meaning they are social rather than natural phenomena.

Romantic love: universal or changeable?

Almost everyone separates out romantic love from other kinds of love or intimacy. This separation is usually about sex: when most people talk about romantic love, they mean love that involves sexual desire.

Many researchers think this kind of love is experienced by all people across time and place, and there is research to support this. Anthropological studies of romantic love across cultures show that love is likely to be a universal human emotion. Neuroscientific investigations of romantic love find similarities in the brain activity or chemistry of people who report being in love.

But the historian William Reddy cautions us not to “make too much of” similarities in romantic love across cultures, and with good reason. There is ample evidence that romantic love varies over time and place.

Cross-cultural studies of romantic love show significant differences in the emotion. And historical investigations almost always demonstrate changes in how people experience or imagine romantic love over time. Is romantic love universal or changeable? There is research to support both viewpoints.

Radical or conservative?

Some of the most interesting research into romantic love looks at its personal and political effects. As the sociologist Mary Evans explains, falling in love is meant to take lovers to a new and different place. Studies of people who are in love report that we understand romantic love as transformative.

And researchers sometimes talk about romantic love as a radical or subversive emotion with the potential to transform society. We can see this particularly in investigations of courtly love. Courtly love was a model of “aristocratic courtship” found in the literature of medieval France. Historians of courtly love often talk about it as a kind of radical resistance to the power of the church.

Others talk about romantic love as a deeply problematic emotion in desperate need of critique. These researchers would say that we may think romantic love is the site of personal freedom, but in fact we are living under “government by love”.

This critique was more common in the 1970s, when radical second-wave feminists attacked heterosexual romantic love as oppressive. But some researchers continue to explain romantic love as one of the ways our lives are regulated and controlled, limiting our intimate possibilities.

I want to know what love is

Some might say all this proves is that we should stop thinking we can research and understand emotions, and just experience them. But I don’t think so. Emotional experiences are a very significant part of our everyday lives, but they also have public and political effects.

Research into emotions gives us insight into the shape of these effects. It shows us the way that war widows were mobilised by their grief in 20th-century Australia, or how acknowledgements of national guilt for past injustices might lead to restitution for the disenfranchised.

Research into romantic love is built on people’s experiences and understandings of their intimate lives. What if love seems muddy in this research because people’s understandings and experiences of intimacy are muddy? What if the diverse ways that people live their intimate lives cannot be explained by a specific singular category, “romantic love”?

If that’s the case, then we don’t really need to worry about fitting into any particular romantic ideal this Valentine’s Day. And romantic love can be whatever we want it to be. Embrace it, avoid it, remake it in your own way. Love your partner, your cat, your friends, everyone, nobody. And don’t apologise for it.![]()

Sarah Pinto, Lecturer in Australian Studies, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Wednesday, 6 March 2024

Nuclear output to reach new record by 2025, says IEA

Monday, 9 October 2023

Women aren’t failing at science

Female scientists are often more productive than their male colleagues but much less likely to be recognised for their work. Argonne National Laboratory/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

Lorena Rivera León, United Nations University

Female scientists are often more productive than their male colleagues but much less likely to be recognised for their work. Argonne National Laboratory/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

Lorena Rivera León, United Nations UniversityFemale research scientists are more productive than their male colleagues, though they are widely perceived as being less so. Women are also rewarded less for their scientific achievements.

That’s according to my team’s study for United Nations University - Merit on gender inequality in scientific research in Mexico, published as a working paper in December 2016.

The study, part of the project “Science, Technology and Innovation Gender Gaps and their Economic Costs in Latin America and the Caribbean”, was financed by the Gender and Diversity Fund of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).

The ‘productivity puzzle’

The study, which looked at women’s status in 42 public universities and 18 public research centres, some managed by Mexico’s National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT), focused on a question that has been widely investigated: why are women in science less productive than men, in almost all academic disciplines and regardless of the productivity measure used?

The existence of this “productivity puzzle” is well documented, from South Africa to Italy, but few studies have sought to identify its possible causes.

Our findings demonstrate that, in Mexico at least, the premise of the productivity puzzle is false, when we control for factors such as promotion to senior academic ranks and selectivity.

Using an econometric modelling approach, including several macro simulations to understand the economic costs of gender gaps to the Mexican academic system, our study focused on researchers within Mexico’s National System of Researchers.

A presentation on Mexican government funding for scientific investment. How many women can you count? Government of Aguascalientes/flickr, CC BY-SA

A presentation on Mexican government funding for scientific investment. How many women can you count? Government of Aguascalientes/flickr, CC BY-SAAdditionally, despite the common belief that maternity leaves make women less productive in key periods of their careers, female researchers in fact have only between 5% to 6% more non-productive years than males. At senior levels, the difference drops to 1%.

Nonetheless, in the universities and research centres we studied, Mexican women face considerable barriers to success. At public research centres, women are 35% less likely to be promoted, and 89% of senior ranks were filled by men in 2013, though women comprised 24% of research staff and 33% at non-senior levels. Public universities do slightly better (but not well): female researchers there are 22% less likely to be promoted than men.

Overall, 89% of all female academics in our sample never reached senior levels in the period studied (2002 to 2013).

In some ways this data should not be surprising. Mexico ranks 66th out of 144 in the World Economic Forum’s 2016 Global Gender Gap Report and a 2015 report by the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) showed that among OECD countries Mexico has the widest overall gender gap in labour participation rates.

Some efforts are being made to improve gender equality in research. In 2013 Mexico amended four articles of its Science and Technology Law to promote gender equality in those fields, adding provisions to promote gender-balanced participation in publicly funded higher education institutions and collect gender-specific data to measure the impact of gender on science and technology policies.

Several CONACYT research centres have launched initiatives to promote gender equality among staff, but many of these internal programmes are limited to anti-discrimination and sexual harassment training.

More aggressive programmes include: the Research Centre on Social Anthopology’s graduate scholarship programme, in collaboration with CONACYT and the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples, to promote higher education and training among indigenous women; and policies to increase women’s participation in higher academic ranks and management at the CIATEQ technological institute, which also gives childcare subsidies to female staff.

But such examples are rare. Overall, women hoping to succeed in Mexican academia must work harder and produce more than their male colleagues to be even considered for promotion to senior ranks.

This persistent inequality has implications not just for women but for the country’s scientific production: if Mexico were to eliminate gender inequality in promotions, the national academic system would see 17% to 20% more peer-reviewed articles published.

A global glass ceiling

Mexico is not alone. Our previous research in France and South Africa, using the same econometric model, found that gender inequalities there also prevent women scientists from being promoted to higher academic ranks.

Examining French physicists working in the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and in French public universities, we learned that female physicists in CNRS are as productive as their male colleagues or more so. Yet they are 6.3% less likely to be promoted within CNRS and 16.3% within universities. This is notable in a country that ranks 17th in the world in gender equality, according to the World Economic Forum.

Black women face more barriers to advancement in the sciences than white women. World Bank Photo Collection/flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

Black women face more barriers to advancement in the sciences than white women. World Bank Photo Collection/flickr, CC BY-NC-SAIn Uruguay the same IDB gender gaps project identified a glass ceiling as well. There women are underrepresented in the highest academic ranks and have a 7.1% less probability than men of being promoted to senior levels.

Moreover, from Mexico and Uruguay to France and South Africa, a vicious cycle between promotion and productivity is at play: difficulties in getting promoted reduce the prestige, influence and resources available to women. In turn, those factors can lead to lower productivity, which decreases their chances of promotion.

This two-way causality creates a source of endogeneity biases when including seniority as a variable to explain productivity in an econometric model. Only when we control for this, as well as for a selectivity bias (that is, publishing occurrence), do we find that female researchers are more productive than their male counterparts. Without these corrections, a gender productivity gap of 10% to 21% appears in favour of men.

The view that women are failing at science is commonly held, but evidence shows that, across the world, it’s science that’s failing women. Action must be taken to ensure that female researchers are treated fairly, recognised for their work, and promoted when they’ve earned it.![]()

Lorena Rivera León, Economist and Research Fellow, United Nations University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thursday, 10 August 2023

One year to go: Will the Paris 2024 Olympics see a return to normalcy?

A group of tourists walk past the Olympic rings in front of Paris City Hall with one year until the Paris 2024 Olympic Games opening ceremony, on July 26, 2023. (AP Photo/Christophe Ena) Angela Schneider, Western University; Alan C Oldham, Western University, and Richard Baka, Victoria University

A group of tourists walk past the Olympic rings in front of Paris City Hall with one year until the Paris 2024 Olympic Games opening ceremony, on July 26, 2023. (AP Photo/Christophe Ena) Angela Schneider, Western University; Alan C Oldham, Western University, and Richard Baka, Victoria University  Aaron Brown, from left to right, Jerome Blake, Brendon Rodney and Andre De Grasse pose with their upgraded Tokyo Olympics silver medals during a ceremony in Langley, B.C., on July 29, 2023. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

Aaron Brown, from left to right, Jerome Blake, Brendon Rodney and Andre De Grasse pose with their upgraded Tokyo Olympics silver medals during a ceremony in Langley, B.C., on July 29, 2023. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck International Olympic Committee President Thomas Bach delivers a speech during the IOC invitation ceremony on July 26, 2023 in Saint-Denis, outside Paris. (AP Photo/Aurelien Morissard)

International Olympic Committee President Thomas Bach delivers a speech during the IOC invitation ceremony on July 26, 2023 in Saint-Denis, outside Paris. (AP Photo/Aurelien Morissard) Angela Schneider, Director, International Centre for Olympic Studies, Western University; Alan C Oldham, PhD Student, International Centre for Olympic Studies, Western University, and Richard Baka, Adjunct Fellow, Olympic Scholar and Co-Director of the Olympic and Paralympic Research Centre, Institute for Health and Sport, Victoria University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Angela Schneider, Director, International Centre for Olympic Studies, Western University; Alan C Oldham, PhD Student, International Centre for Olympic Studies, Western University, and Richard Baka, Adjunct Fellow, Olympic Scholar and Co-Director of the Olympic and Paralympic Research Centre, Institute for Health and Sport, Victoria University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.Thursday, 22 June 2023

Nuclear leaders issue call for action from G7 : Energy & Environment

.jpg?ext=.jpg)

- Accelerating the deployment of new nuclear plants

- Supporting international cooperation and the nuclear supply chain

- Developing a financial environment that promotes investment in nuclear power

- Supporting innovative nuclear technology development

- Promoting public understanding of nuclear energy

- Collaborating internationally to share best practices, including working toward the realisation of final nuclear waste disposal

- Supporting countries that have newly introduced, or are considering, nuclear energy.