Learning a new language later in life can be a frustrating, almost paradoxical experience. On paper, our more mature and experienced adult brains should make learning easier, yet it is illiterate toddlers who acquire languages with apparent ease, not adults.

Babies start their language-learning journey in the womb. Once their ears and brains allow it, they tune into the rhythm and melody of speech audible through the belly. Within months of birth, they start parsing continuous speech into chunks and learning how words sound. By the time they crawl, they realise that many speech chunks label things around them. It takes over a year of listening and observing before children say their first words, with reading and writing coming much later.

However, for adults learning a foreign language, the process is typically reversed. They start by learning words, often from print, and try to pronounce them before grasping the language’s overall sound.

Tuning in to a new language

Our new study shows that adults can quickly pick up on the melodic and rhythmic patterns of a completely novel language. It confirms that the relevant native-language acquisition mechanism remains intact in the adult brain.

In our experiment, 174 Czech adults listened to 5 minutes of Māori, a language they had never heard. They were then tested on new audio clips from either Māori or Malay – another unfamiliar but similar language – and asked to say if they were hearing the same language as before or not.

The test phrases were acoustically filtered to mimic speech heard in the womb. This preserved melody and rhythm, but removed the frequencies higher than 900 Hz which contain consonant and vowel detail.

Listeners correctly distinguished the languages more often than not, showing that even very brief exposure was enough for them to implicitly grasp a language’s melodic and rhythmic patterns, much like babies do.

However, during the exposure phase, only one group of participants simply listened – three other groups listened while reading subtitles. The subtitles were either in the original Māori spelling where speech sounds consistently map onto specific letters (similar to Spanish), altered to reduce sound-letter correspondence (like in English, for example “sight”, “site”, “cite”), or they were transliterated to a script unknown to any of the participants (Hebrew).

The results showed that reading alphabetic spellings actually hampered the adults’ sensitisation to the overall melody and rhythm of the novel language, reducing their test performance. As complete beginners, the participants were able to learn more Māori without textual aids of any kind.

Initial illiteracy helps learning

Our research builds on previous studies, which have found that spelling can interfere with how learners pronounce individual vowels and consonants of a non-native language. Examples among learners of English include Italian learners lengthening double letters, or Spaniards confusing words like “sheep” and “ship” due to how “i” and “e” are read in Spanish.

Our study shows that spelling can even hinder our natural ability to listen to speech melody and rhythm. Experts looking for ways to reawaken adults’ language-learning capabilities should therefore consider the potentially negative impact of premature exposure to alphabetic spelling in a foreign language.

Early studies have proposed that a putative “sensitive period” for acquiring the sound patterns of a language ends around age 6. Not coincidentally, this is the age when many children learn to read. There is also research on infants that shows that starting with the global features of speech, such as its melody and rhythm, serves as a gateway to other levels of the native language.

A reversed approach to language learning – one that begins with written forms – may indeed undercut adults’ sensitisation to the melody and rhythm of a foreign language. It affects their ability to perceive and produce speech fluently and, by extension, other linguistic competences like grammar and vocabulary usage.

A study with first- and third-graders confirms that illiterate children learn a new language differently from literate children. Non-readers were much better at learning which article went with which noun (like in the Italian “il bambino” or “la bambina”) than at learning individual nouns. In contrast, readers’ learning was influenced by the written form, which puts a space between articles and nouns.

Learn like a baby

Listening without reading letters may help us to stop focusing on individual vowels, consonants and separate words, and instead absorb the overall flow of a language much like infants do. Our research suggests that adult learners might benefit from adopting a more auditory-focused approach – engaging with spoken language first before introducing reading and writing.

The implications for language teaching are significant. Traditional methods often place a heavy emphasis on reading and writing early on, but a shift toward immersive listening experiences could accelerate spoken proficiency.

Language learners and educators alike should therefore consider adjusting their methods. This means tuning in to conversations, podcasts, and native speech from the earliest stage of language learning, and not immediately seeking out the written word.![]()

Kateřina Chládková, Assistant professor, Charles University; Šárka Šimáčková, assistant professor, Palacky University Olomouc, and Václav Jonáš Podlipský, Assistant Professor of English Phonetics, Palacky University Olomouc

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

SWNS

SWNS SWNS

SWNS

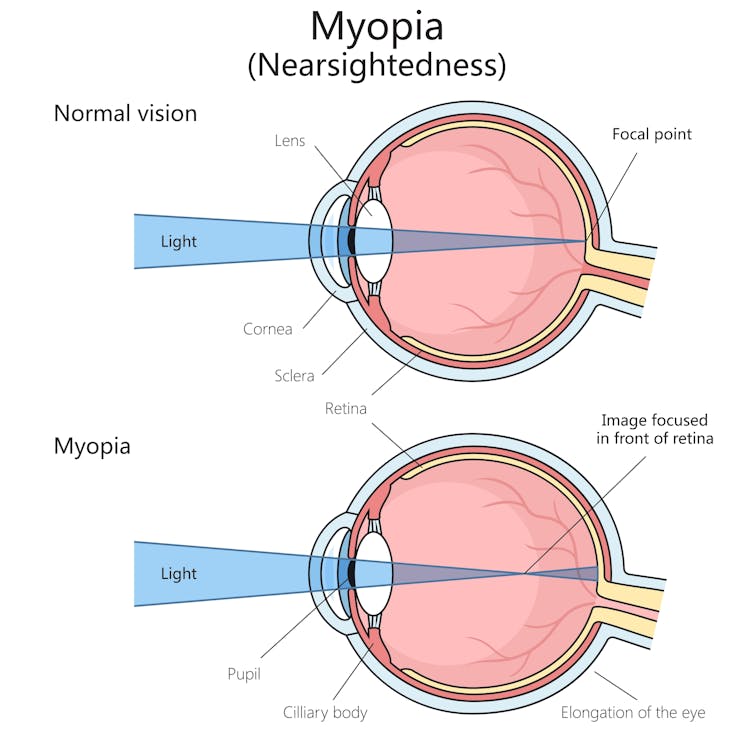

Myopia is a common vision problem.

Myopia is a common vision problem.  Sunlight may play a role in slowing myopia progression.

Sunlight may play a role in slowing myopia progression.  You can monitor your child’s eye health and vision with regular eye tests.

You can monitor your child’s eye health and vision with regular eye tests.

SWNS

SWNS