Thursday, 3 April 2025

Shakira concerts give multimillion-dollar boost to Mexico

Monday, 17 March 2025

Shakira cancels Colombia concert over venue safety concerns

Friday, 21 February 2025

Shakira kicks off first world tour in seven years

Tuesday, 18 February 2025

Chennai-born New Yorker Chandrika Tandon wins Grammy for Best New Age Album

Music producer put up a group photo at the Grammys on Instagram. PHOTO: Screenshot from Instagram via ANI

Music producer put up a group photo at the Grammys on Instagram. PHOTO: Screenshot from Instagram via ANI Chennai-born Chandrika Tandon wins Grammy for Best New Age AlbuM ‘Triveni’. PHOTO: Instagram @chandrikatandon

Chennai-born Chandrika Tandon wins Grammy for Best New Age AlbuM ‘Triveni’. PHOTO: Instagram @chandrikatandonThursday, 5 December 2024

The harsh process of becoming a K-pop star is opening to western performers

Made in Korea: The K-Pop Experience is a six-part reality show following five British trainees over 100 days as they debut as a Korean-pop (K-pop) idol boy group called Dear Alice. In collaboration with SM Entertainment, a K-pop powerhouse, the show will introduce the behind-the-scenes of making a K-pop idol through an immersive training system.

Showing a glimpse of the lives of K-pop trainees, the first episode introduces K-pop as a multi-billion global phenomenon, stating: “Six of the top 20 best-selling artists in the world were K-pop and 90 billion streams were by K-pop idols.”

K-pop is becoming increasingly popular in the UK. Girl group Aespa and boy group BTS have sold out shows in the country’s largest arenas.

In 2023, the group Blackpink became the first Korean band to headline a UK festival at BST Hyde Park, where they played to an audience of 65,000. They were also awarded honorary MBEs by the king for their role in encouraging young people to engage with the global UN climate change conference at COP26 in Glasgow 2021.

There is certainly an appetite for shows about K-pop for western audiences. Netflix have released their own version of Made in Korea, Pop Star Academy: Katseye.

The docuseries follows 20 girls from Japan, South Korea, Australia and the UK going through a year of K-pop training to become the group Kasteye. It’s a collaboration between the K-pop label Hybe and US label Geffen (a subsidiary of Universal).

Generally speaking, K-pop is characterised by catchy and lively melodies and highly choreographed dance routines in perfect unison and fancy outfits. Inspired by various pop music genres – including but not limited to electronic dance, hip hop, and R&B – the genre became distinctive from the nation’s traditional music, especially after a handful of pioneers began producing idol groups in the 1990s.

I’m South Korean and I’m studying cultural industries, so it’s interesting for me to see westernerss becoming K-pop-inspired idol groups. It’s a famously competitive industry, which is already oversaturated with hopeful K-idols. Considering that the domestic market is small and highly saturated, their success will be a breakthrough for SM Entertainment and HYBE, as well as other K-pop companies, proving whether they can continue to grow beyond east Asia.

The production and delivery of this popular music genre have become more international than ever in recent years, with hundreds of choreographers, composers and producers worldwide contribute to creating K-pop songs and performances. In contrast, K-pop performers have until recently been predominantly Korean. But as the new shows demonstrate, this too is changing.

K-pop companies have hosted auditions outside the country to recruit foreign trainees to make their idols appeal to global audiences. Huge global music corporations like Sony, Universal Music Group and Virgin Records have also got in on the game, signing distribution contracts with major K-pop idols to promote their music in foreign markets.

This search isn’t because there is a lack of willing hopefuls in Korea. There were around an estimated 800 trainees waiting to debut in 2022. But Korea’s population is only around 50 million and record companies want to appeal beyond the domestic market, so they are hoping recruiting non-Korean stars will help do that.

Music agencies in the west tend to find new artists who are already gifted and then largely serve as intermediaries arranging things like tours, marketing and artists’ wider schedules. However, major K-pop companies have developed a unique system of finding and launching new artists. This involves hosting auditions with a competition of at least 1,000 to 1 odds. The winners then undergo years of of acting, vocal, and dance training before debuting.

To make the vocals flawless and the dance moves precise, trainees, known as yeonseupsaeng (연습생), are expected to spend up to 17 hours per day practising performances and training for several years – although they aren’t guaranteed to become professional artists. Even if they do become successful, their private lives – including their dating lives – are strictly controlled.

It is no exaggeration to say that the industry is labour-intensive as well as capital-intensive, built on the blood, sweat and tears of yeonseupsaeng.

The first episode of Made in Korea ends with SM’s director Hee Jun Yoon’s critique of the Britons’ first performance. It’s difficult viewing for those unfamiliar with the harsh world of K-pop. To borrow the words of BBC’s unscripted content head, Kate Phillips, it makes “Simon Cowell look like Mary Poppins.”

Some might question the prefix “K-” being used to describe these international groups but the genre will remain decidedly Korean. It is Korean companies which will lead the production mechanisms and the domestic market will continue to serve as the testbed for new artists. But the success of Dear Alice and Katseye is important if the genre is to survive and continue to grow beyond Korea.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.![]()

Taeyoung Kim, Lecturer in Communication and Media, Loughborough University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sunday, 29 September 2024

When Music Festival Ticket Holders Couldn’t Get a Refund, Another Festival Welcomed Them for Free

Wednesday, 25 September 2024

David Bowie's handwritten 'Starman' lyrics sell for over £200,000

LONDON - David Bowie's original handwritten lyrics for the pop classic "Starman", part of an album that catapulted him to international stardom, on Tuesday sold at auction in Britain for £203,500.

LONDON - David Bowie's original handwritten lyrics for the pop classic "Starman", part of an album that catapulted him to international stardom, on Tuesday sold at auction in Britain for £203,500.Tuesday, 24 September 2024

Why are the violins the biggest section in the orchestra?

As the largest section of the orchestra, sitting front and centre of the stage performing memorable melodies, it’s easy for violinists to steal the limelight. Ask any violinist why there are so many in an orchestra, and we’ll often reply, tongue-in-cheek: “obviously it’s because we’re the best”.

The real answer is a bit more complex, and combines reasons both logistical and historical.

How we got the modern orchestra

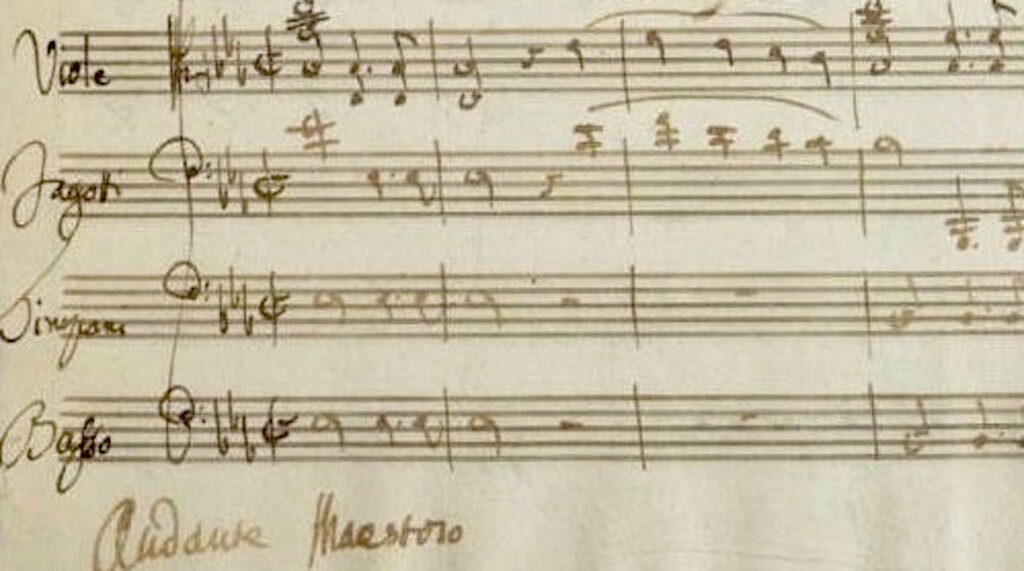

During the Baroque period between around 1600 and 1750, the composition of the orchestra was not standardised, and often used instruments based on availability. Monteverdi’s opera L'Orfeo, which premiered in 1607, is one of the earliest examples of a composer specifying the desired instrumentation.

The size of the orchestra also varied. Johann Sebastian Bach wrote for and worked with ensembles of up to 18 players in Germany. At Palazzo Pamphili in Rome, Corelli directed ensembles of 50–80 musicians – and, on one notable occasion to celebrate the coronation of Pope Innocent XII, an ensemble of 150 string players.

The modern-day violin was also developed around this time, and eventually replaced the instruments of the viol family. The violin has remained a staple member of the orchestra ever since.

Philippe Mercier, 1689 or 1691–1760, Franco-German, active in Britain (from 1716), The Sense of Hearing, 1744 to 1747, Oil on canvas. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1974.3.19.

Philippe Mercier, 1689 or 1691–1760, Franco-German, active in Britain (from 1716), The Sense of Hearing, 1744 to 1747, Oil on canvas. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1974.3.19.Music of this period was created on a smaller scale than much of the repertoire we hear today, and often placed a strong focus on string instruments. As the orchestra became more standardised, members of the woodwind family appeared, including the oboe, bassoon, recorder and transverse flute.

During the classical period from around 1730 to 1820, orchestral performances moved from the royal courts into the public domain, and their size continued to grow. Instruments were organised into sections, and bowed strings formed the majority.

Composers began to use a wider range of instruments and techniques. Beethoven wrote parts for the early double bassoon, piccolo flute, trombone (which was largely confined to church music beforehand), and individual double bass parts (where previously they had often doubled the cello part).

Marco Ricci, 1676–1729, Italian, active in Britain (1708–10; 1711–16), Rehearsal of an opera, ca. 1709, Oil on canvas. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1981.25.523.

Marco Ricci, 1676–1729, Italian, active in Britain (1708–10; 1711–16), Rehearsal of an opera, ca. 1709, Oil on canvas. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1981.25.523.During the romantic period of the 19th century, composer Hector Berlioz, author of a Treatise on Instrumentation and Modern Orchestration (1841), further developed the symphony orchestra by adding instruments such as the tuba, cor anglais and bass clarinet.

By the end of the 19th century, many orchestras reached the size and proportions we recognise today, with works that require more than 100 musicians, such as Wagner’s Ring Cycle.

What’s size got to do with it?

As increasing numbers of performers and instruments became standard in orchestral repertoire, ensembles became louder, and more string players were needed to balance the sound. The violin is a comparatively quiet instrument, and a solo player cannot be heard over the power of the brass.

Having violinists at the front of the stage also helps the sound reach the audience’s ears without competing to be heard over the louder instruments.

The typical layout of the orchestra has not always been standard. First violinists (who often carry the melody) and second violinists (who typically play a supportive role) used to sit opposite each other on stage.

US conductor Leopold Stokowski rearranged the position of the first and second violinists during the 1920s so they sat next to each other on the left of the stage. This change meant the voices of each string section were arranged from high to low across the stage.

This change was widely adopted and has become a standard setup for the modern orchestra.

Stokowski is known for experimenting with the layout of the orchestra. He once placed the entire woodwind section at the front of the orchestra ahead of the strings, receiving widespread criticism from the audience and musicians. The board of the Philadelphia Orchestra allegedly said the winds “weren’t busy enough to put on a good show”.

Sound, texture and timbre

String players do not need to worry about lung capacity or breaking for air. As such, violinists can perform long melodic passages with fast finger work, and our bows allow for seemingly endless sustain. Melodies written for strings are innumerable, and often memorable.

Having several violinists play together creates a specific sound and texture that is distinct from a solo string player and the other sections of the orchestra. Not only is the sound of every violin slightly different, the rate of each string’s vibration and the movement of each player’s bow varies. The result is a rich and full texture that creates a lush effect.

Today, symphony orchestras are expected to perform an incredibly diverse range of repertoire from classical to romantic, film scores to newly commissioned works. Determining the number of violinists who will appear in any given piece is a question of balance that will change depending on the repertoire.

A Mozart symphony might require fewer than ten wind or brass players, who would be drowned out by a full string section. However, a Mahler symphony requires more than 30 non-string players – meaning far more string players are needed to balance out this sound.

Room for experimentation

Notable exceptions to the orchestra’s standard setup include Charles Ives’ 1908 The Unanswered Question for string orchestra, solo trumpet and wind quartet spread around the room; Stockhausen’s 1958 Gruppen, pour trois orchestres, in which three separate orchestras perform in a horseshoe shape around the audience; and Pierre Boulz’s 1981 Répons featuring 24 performers on a stage surrounded by the audience, who are in turn surrounded by six soloists.

Despite experimentation, the placement and number of instruments in an orchestra has remained relatively standard since the 19th century.

Many aspects of the traditional orchestra’s setup make sense. However, many of the orchestra’s habits come down to tradition and perhaps unconscious alignment with “just the way things are done”.![]()

Laura Case, Lecturer in Musicology, Sydney Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Monday, 9 September 2024

Justin Bieber, wife Hailey announce birth of their first baby: Welcome home Jack Blue Bieber

Thursday, 29 August 2024

Dua Lipa recalls how she went through 'two years of humiliation' over her dancing

Wednesday, 28 August 2024

Classical Music Lifts Our Mood by ‘Synchronizing’ Parts of the Brain, Says Study of Patients with Depression

Tuesday, 6 August 2024

Be Free: A child’s prayer for freedom and life

“Be Free” – a testimonial song by Lemuel J Philip was released on Monday evening in his YouTube channel @LemuelJPhilip. This is Lemuel’s first song.

Saturday, 3 August 2024

Country music star Jason Michael Carroll selected as Harvest Festival entertainer

Tuesday, 23 July 2024

The magic of audio deepening travel experience with kids

Thursday, 4 July 2024

Virie: Winning hearts with soulful voice

Wednesday, 3 July 2024

Music platform CEO says AI is not the enemy

Tuesday, 14 May 2024

Musical band of Varsha Joshi gets high praise for Mother’s Day event

Sunday, 28 April 2024

‘Connecting Musicians’ fellowship in Kohima

Monday, 25 September 2023

Reality TV show contestants are more like unpaid interns than Hollywood stars

Country singer Adley Stump, a former contestant on NBC’s hit reality show ‘The Voice,’ performs at an Air Force base in Washington state. Joint Base Lewis McChord/flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

David Arditi, University of Texas at Arlington

Country singer Adley Stump, a former contestant on NBC’s hit reality show ‘The Voice,’ performs at an Air Force base in Washington state. Joint Base Lewis McChord/flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

David Arditi, University of Texas at ArlingtonIn December 2018, John Legend joined then-newly elected U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to criticize the exploitation of congressional interns on Capitol Hill, most of whom worked for no pay.

Legend’s timing was ironic.

NBC’s “The Voice” had just announced that Legend would join as a judge. He would go on to reportedly earn US$14 million per season by his third year on the show. Meanwhile, all of the participants on “The Voice,” save for the winner, earned $0 for their time, apart from a housing and food stipend – much like those congressional interns.

The fall 2023 TV lineup will be saturated with low-cost reality TV shows like “The Voice”; for networks, it’s an end-around to the ongoing TV writers and actors strikes.

Whether it’s “The Voice,” “House Hunters,” “American Chopper” or “The Bachelorette,” reality shows thrive thanks to a simple business model: They pay millions of dollars for big-name celebrities to serve as judges, coaches and hosts, while participants work for free or for paltry pay under the guise of chasing their dreams or gaining exposure.

These participants are the unpaid interns of the entertainment industry, even though it’s their stories, personalities and talent that draw the viewers.

Dreams clash with reality

To conduct research for my book, “Getting Signed: Record Contracts, Musicians, and Power in Society,” I interviewed musicians around the country.

The book was about the exploitative nature of record contracts. But during my research, I kept running into singers who had either auditioned for or participated in “The Voice.”

On “The Voice,” singers compete on teams headed by a celebrity coach. Following a blind audition and various elimination rounds, the live broadcasts begin with four teams of five members apiece. These 20 contestants spend months working in Los Angeles and are provided with only their room and board. Each week, at least one player is eliminated. At the end of each season, the winner receives $100,000 and a record contract.

While some viewers might see reality shows like “The Voice” as launching pads for music careers, many of the musicians I spoke with were disheartened by their experiences on the show.Contestants audition for ‘The Voice’ ahead of its 24th season.

Unlike “American Idol,” where a number of winners, from Kelly Clarkson to Jordan Sparks, have made it big, no winners of “The Voice” have become stars. The closest person to “making it” from “The Voice” is the controversial country singer Morgan Wallen, who was infamously dropped by his label and country radio following the emergence of a video of him using a racial slur. And Wallen didn’t even win “The Voice”; in fact, he barely made it past the blind audition.

Former contestants repeatedly told me that the television exposure did little to help their careers.

Prior to joining the show, many of the musicians were trying to scratch out a living through touring or performing. They put their developing careers on pause to chase their dreams.

However, the show’s contracts have stipulated that contestants cannot perform, sell their name, image and likeness, or record new music while on “The Voice.” (The Conversation reached out to NBC to see if this remains the case for the current season, but did not receive a comment.)

This leaves the 20 finalists with no means to sell their music, even as they spend up to eight months competing. When the show’s losers return to performing, many of them have little new material to promote. By the time they drop a new single or album and announce a tour, some of them told me that they had lost a good portion of their following.

There is one group of people who receive meaningful exposure from these shows: the coaches and judges. Several singers, such as Gwen Stefani and Pharell Williams, have used “The Voice” to jolt their stagnating music careers. While earning millions as coaches and judges, these stars even use the show to promote their music – something the contestants themselves are barred from doing.

Paying these contestants is feasible. If Legend earned $13 million instead of $14 million, that spare million dollars could be dispersed to half of the contestants at $100,000 apiece – an amount that’s currently only reserved for the winner of the show. Cut the salaries of all four coaches by $1 million apiece, and it would free up enough money to pay all 20 contestants $200,000 each.

A gold mine for networks

“The Voice” is far from the only reality show to take advantage of the genre’s low overhead costs.

Over the past two decades, shows featuring Americans looking to buy houses or remodel their homes have exploded in popularity. HGTV cornered this market by creating popular shows such as “House Hunters,” “Flip or Flop” and “Property Brothers.”

Viewers might not realize just how profitable these shows are.

Take “House Hunters.” The show follows a prospective homebuyer as they tour three homes. Homebuyers featured on the show have noted that they earn only $500 for their work, and the episodes take three to five days and about 30 hours to film. The show’s producers don’t pay the realtors to be on it.

The low pay for people on reality TV shows matches the low budget for these shows. A former participant wrote that episodes of “House Hunters” cost around $50,000 to film. Prime-time sitcoms, by comparison, have a $1.5 million to $3 million per episode budget.

Sidestepping the unions

That massive budget gap between reality TV and sitcoms is not simply due to an absence of star actors.

Many scripted television shows are based in Los Angeles, where camera crews, stunt doubles, costume artisans, makeup artists and hair stylists are unionized. But shows like “House Hunters,” which are filmed across the country, will recruit crews from right-to-work states. These are states where employees cannot be compelled to join a union or pay union dues as a condition of employment. For these reasons, unions have far less power in these states than they do in places traditionally associated with film and entertainment, such as California and New York.

That’s one reason why TV production started moving to Atlanta – what’s been dubbed the “Hollywood of the South” – where shows like “The Walking Dead” and “Stranger Things” have been filmed.

But in my research, I also learned that Knoxville, Tennessee, has become a reality TV mecca. Like Georgia, Tennessee is also a right-to-work state. In Knoxville, many working musicians join the city’s low-paying entertainment apparatus by taking gigs working on TV and film production crews in between shows and tours.

At a time when TV writers and actors are on strike, it is important to understand that the entertainment industry will try to exploit labor for profit whenever it can.

Reality TV is a way to undercut the leverage of striking workers, whether it’s through their lack of unionized actors, or their use of nonunionized production crews.

With actors and writers on strike, many networks and streaming services are featuring reality TV-heavy fall lineups. David McNew/Getty Image

With actors and writers on strike, many networks and streaming services are featuring reality TV-heavy fall lineups. David McNew/Getty ImageContestants, casts and crew members are starting to catch on. Many reality TV participants have said that they feel like strike scabs, and Bethenny Frankel of “Real Housewives” is reportedly trying to organize her fellow reality performers.

Preying off contestants who are desperate for exposure, reality TV might just be the next labor battle in the entertainment industry.

As John Legend put it, “Unpaid internships make it so only kids with means and privilege get the valuable experience.”

Reality TV does the same to aspiring actors, musicians and celebrities.![]()

David Arditi, Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Texas at Arlington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Sunday, 9 October 2022

Shakira to stand trial in Spain for tax evasion